Five questions for Megan Friedel

Every day is a treasure hunt for Megan Friedel, as she and her colleagues make sense of people’s lives from the scraps of information left behind. Those bits and pieces might be diaries or other personal writings, recordings or even a wealth of social-media posts. One of her goals at University Libraries’ Archives at CU Boulder is to find and document the stories of those who haven’t traditionally had their stories represented in the archival record.

“The thing I am most passionate about right now is filling in the gaps in our archival records,” she said. “Archives, by their very nature, are places of power and privilege. Traditionally, what has been documented are the stories of people in power, so, to put it bluntly, mostly white men.”

As head of archives, Friedel also works to make the 50,000 linear feet of the collections (about 9.5 miles, or from Boulder to Louisville, if laid end to end) accessible to all in 21st century ways.

She has spent 18 years in the archival profession, including positions at History Colorado and other state historical societies and at another university.

“One of the most exciting things about coming to CU two years ago was the collection,” she said. “We have one of the oldest and largest collections of archival material in the state of Colorado. We’ve been collecting since 1918.”

The efforts to gather materials continues. An ongoing collaboration with a program in Jewish Studies, for instance, is working to find more information for the Innovation in Jewish Life Collection, which reflects the interesting and innovative ways that Jewish culture has thrived, particularly post-World War II.

Another collaboration, this time with the College of Music, aims to collect American popular music through CU’s American Music Research Center collections, and this includes documenting Colorado’s rich musical history and counterculture.

Friedel said the archives also are building a collection of experimental film based around Stan Brakhage’s work, which has been housed at CU for many years. (Brakhage is considered one of the most important figures in 20th-century experimental film.)

Friedel grew up in a family with deep, well-documented historical roots – immigrants from Sicily and Germany, Colombia and Peru, England and Ireland.

“I am the great-great-great granddaughter, on my mom’s side of the family, of Francisco Jose de Paola Santander, the first president of Peru after its independence from Spain,” she said. “My grandparents had so much in their house – books, diaries, photos, etc. – documenting that part of our family’s history, as well as other roots going back to the American Revolution. Growing up around all that raw material of my family’s past was why I got into the profession.”

Norlin Library and the archives currently are closed to protect patrons and staff from the novel coronavirus, but Friedel and her colleagues in both the Archives and Special Collections are working. Their newest project is documenting how we’re coping with COVID-19.

Statewide stay-at-home orders also have given her a chance to spend a little more time doing other things she loves. She and her husband are musicians – she, a flat-picking guitarist; he, a bass player – active in Colorado’s bluegrass community. She also takes her toddler out each morning, exploring the wilderness on unmarked trails looking for, what else, treasures.

1. You mentioned that you want to document stories of people who traditionally are underrepresented. What are some of the ways you are doing this?

Right now, my colleagues Adam Lisbon and Dave Hayes and I are working on the CU Japanese and Japanese American Community History project. We are actively reaching out to members of the Japanese and Japanese American community via faculty, alumni, current students and retired staff to gather stories of what it has been like to be Japanese and Japanese American on campus since the early 20th century to the present, because we don’t have that in the record. I also have been supporting efforts to commemorate Los Seis de Boulder, the six Chicano activists and students who died in the May 1974 bombings, to really bring that vital part of Chicanx history on campus into the archival record because it has been either hidden in larger collections or just hasn’t been collected. It is such an important part of the late ’60s and ’70s on our campus.

We know that communities like the Chicanx community are not naturally going to come to the CU archive to donate their materials, and some of that has to do with distrust of the administration of CU or with the trepidation that people naturally have about approaching the archive. A lot of what we do is relationship-building – reaching out to communities to build that trust and create safe spaces within the archives that people feel comfortable with in terms of donating their materials.

We also have a lot of people who independently reach out to us with information. We are seeing, at least anecdotally, a huge uptick in donations that are being offered to us. My colleague Debbie Hollis, who is head of special collections, and I are doing research to put solid numbers around this because, as we suspect, we are at the tail end of the baby boomer generation. A lot of that generation is looking to move out of their homes, to downsize, or is thinking about end-of-life plans, and they are looking for a place for their family history or the materials they’ve collected.

2. Recently, Gov. Jared Polis donated his congressional library collection to CU. What processes are you going through to archive the materials and why won’t some items of that collection be accessible to the public for several decades?

The Jared Polis collection is an interesting one. Colorado politics in the 20th and 21st century is a collecting area for us; we have papers of Ken Salazar, Pat Schroeder and Mark Udall, among others. Udall had shared with Jared that he had given his congressional collection to us. I think that is why Jared reached out to us.

We were willing to work with him on the restrictions that he wanted to place on the collection. Such restrictions are highly unusual. We are a public archive at a public university, and so I feel a very strong mandate, even if it is not explicitly written, that we make our collections as accessible as possible to our community, our researchers and our campus community. But Polis’ team was set on restricting materials for 35 years. The materials are those that primarily were produced for his office when he was in Congress, such as his speeches and position papers.

We normally would not accept a collection with restrictions on it, but we did want to take this and keep it in perpetuity because we know that once it gets opened up, it will be a really important collection for the history of politics in Colorado and the nation, especially considering he is the first openly gay governor in the country.

We did something innovative in that we worked with our digital archivist Walker Sampson to archive Jared Polis’ congressional social media accounts and his web page. Those are available to the public now. We were able to capture Polis’ Twitter account, Instagram, Facebook, Medium and his website in real time in the late days of him being in office. (Visit https://archive-it.org/collections/11542)

When we get a collection like this, our archivists who work with manuscript and digital materials create a basic inventory so we have a rough idea of what is in the collection. Normally, we would make it accessible immediately. The more detailed organization of a collection takes a lot longer and depends on the size and content of the collection, but we are committed to making sure that the collections become available as soon as we can. We don’t want them sitting in storage for decades, which certainly has happened in the past.

Polis’ collection was well-organized, but we often get boxes from people’s garages and basements where the person literally emptied the contents of their desks into a box. It could be anything from diaries to papers to journals to sound recordings, moving image films or photographs. That’s where the detailed work comes in, trying to figure out what the material is and how we organize it in a way that will make sense for researchers. That takes a lot more time and a lot more work, but that is the reason we all became archivists, to really dig into the stuff of history and to re-create someone’s life or an organization’s history or an event. That is the fun stuff.

3. What is a collection in the archives that you found fascinating?

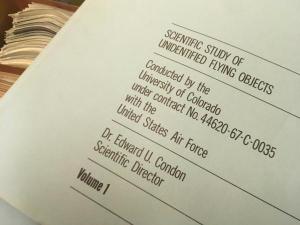

Probably my favorite weird collection is Edward Condon’s collection. He was a professor of nuclear physics and astrophysics who died in 1974. He was a fellow at the Joint Institute of Laboratory Astrophysics (JILA) at CU. He was well-known for his participation in the development of radar and nuclear weapons. In the mid-1960s, he conducted a study of Unidentified Flying Objects (UFOs) for the United States Air Force. His report was issued in 1968, and we have the report and a number of other related items like UFO publications and other reports and journals. He did everything from interview the people who claimed to have seen UFOs to people who claimed to have been abducted by aliens. The fact that this was produced for the Air Force and was done while he was at CU and considered to be part of his work is what is fascinating.

4. What are you doing to document COVID-19 and how it has affected our lives?

In early March, my colleague Susan Guinn-Chipman in the University Libraries’ Special Collections saw the importance of trying to document how our campus is responding to COVID-19.

In real time, our Archives and Special Collections faculty and staff are now creating an active, ongoing archive of student, faculty and administrative responses to this significant moment in our history. Our digital archivist is capturing and archiving digitally all the news stories about CU and the announcements coming from campus administrators. We’re also working with our student employees who are documenting their personal experiences of what it is like living during this time, both on campus and, now, at home. Our Special Collections folks are working with our faculty in the history and English departments to archive student projects about COVID-19 that faculty are assigning during this online, remote-education period.

We’re going to try to make at least the first round of material we are collecting available later this spring online. I’m really proud of the way our Special Collections and Archive teams, led by Susan and our collection development archivist, Kalyani Fernando, have jumped into this and put a project together in very little time, all while facing challenges at home and at work.

5. What advice would you give to the general public about “archiving” their family items?

We’re lucky in Colorado to have low humidity, so you can throw things in a box and store it in a garage or the basement. High humidity can destroy documents.

The big thing I would tell people is don’t throw things out. People have a tendency to think they don’t need to keep a physical photograph because they have scanned it as a digital copy. But think about the floppy disks that you were using in the 1980s to store records. Can you access those now? Probably not; at least not on your own. Why do you think that trying to access a digital image in 20 years will be different? It is much better to hold onto that original, which is where the historical value is. That’s where the beauty of history is found. Do create a scan for your family to share, but don’t consider that preservation.

If something records a moment in your family history that you think is important to future generations that says something about who you are or where your family came from – that is a core part of your family history – keep it; don’t throw it out. Think about how you want to store it for future generations and consider donating it to a public institution if you are comfortable with it being part of the bigger picture and the bigger story.