Five questions for Mary Guy

What makes a fireman or policeman rush to help others each and every day? How do they – and others in high-stress jobs -- continue to enjoy their work? And what can be done to prevent the slow and steady decline that leads to burnout?

These and other questions piqued the interest of Mary Guy, a professor at the School of Public Affairs at the University of Colorado Denver, and her research on the subject has led to numerous publications, including a recent co-authored book, “Emotional Labor and Crisis Response: Working on the Razor’s Edge.”

Guy was a public service executive for many years, but as she gained experience, she became curious about the interplay of theories, research and practice. “Before long I was working for the state government during the day and sitting in doctoral classrooms over my lunch hours and in the evenings and weekends.”

During doctoral studies, she realized how much she loved the window into theory and research that the academic life provided, and after earning her Ph.D., left her administrative post and took a faculty position. She worked for several years at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, where she served as department head, and held the Jerry Collins Eminent Scholar Chair at the Askew School of Public Administration and Policy at Florida State University.

“When former Dean Kathleen Beatty offered me the opportunity to move my work to (CU Denver), I decided that was an opportunity too good to pass up. I had watched from afar as the School of Public Affairs had grown in stature and prominence in the field and I had never lived in the West. So this was a chance to carry on my work in a well-respected program as well as enjoy new sights and experiences,” said Guy, who began working at CU in the fall of 2008.

“On the Razor’s Edge” is her second book on emotional labor. She and her colleagues are using their research findings to recommend improvements in human resource functions, including compensation.

1. What is emotional labor and what types of workers must incorporate it into their jobs?

Emotional labor is a term used for the invisible work that has to be done on the job in order to “grease the wheels” when interacting with others, whether they are co-workers, clients, customers, students or patients. It involves managing one’s own emotions in order to display the “proper” emotion in any given situation and it also involves sensing and appropriately responding to the emotional state of the person with whom one is interacting. All this is done in order to get the job done.

2. What are the most important issues/pitfalls surrounding emotional labor? How can these be reduced or avoided?

Most people confuse emotional labor with burnout. In fact, working in emotionally intense situations can lead to burnout. That is its downside. But it also leads to the highest levels of job satisfaction. My research has revealed how emotional labor supplies the “juice” that causes first responders, for example, to be able to go to work each day, not knowing what they will confront, but at the same time knowing that their work will make a difference that will last a lifetime.

I have interviewed a number of public service workers in Colorado and elsewhere whose performance on the job is awesome. From Victim Assistance Counselors to domestic violence workers to law enforcement officers to firefighters to prison wardens to Coast Guard officers to school teachers, the stories they tell of “the best day of their lives” and “the worst day of their lives” revolve around emotionally intense situations where they were called upon to perform emotional labor in extremis. Their stories are instructive and advance our understanding of what it takes to work in public service, day in and day out, at the street level.

3. How did you choose to study this subject?

One of my research agendas has been, and remains, to understand why women’s salaries remain lower than men’s. When I first learned of emotional labor, I naively assumed that this might be the key that would unlock the answer to the question. I had assumed that women’s jobs required emotional labor (but did not compensate for it), while men’s jobs did not. I was soon disabused of that notion. In fact, both women and men are called upon to perform emotion work, albeit in different forms. I still am seeking the answer about pay inequity while my research into emotional labor has as its goal to make the role of emotion work skills explicit in the workplace, in job descriptions, in training and development, and in compensation.

4. What are some of your outside interests?

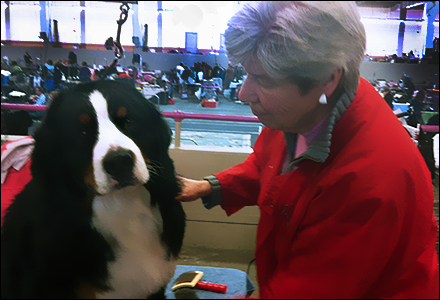

I’ve gone to the dogs. My favorite hobby is showing my Bernese Mountain Dogs and being active in local kennel clubs. Throughout my academic life, I have found that having a hobby -- about which I am passionate -- takes me far enough away from workplace frustrations that my outlook stays balanced.

5. Do you have a motto that you live by?

From Eleanor Roosevelt: “You must do the thing you think you cannot do.” These words have given me the courage to reach farther, dig deeper, and do more. They worked for me yesterday and they will work for me tomorrow.