Cancer investigators, postdoc students take on aggressive disease

People diagnosed with some of the most aggressive forms of thyroid cancer often live less than one year because of the limited number of effective therapies available to them.

What makes these types of cancer so aggressive?

It’s a question that Thomas Beadnell hopes to find answers to through his studies in the lab of Rebecca Schweppe at the School of Medicine on the CU Anschutz Medical Campus. Beadnell is a graduate student beginning his fifth year in a program that grooms young scientists to become the next generation of leading cancer researchers.

The Training Program in Cancer Biology is directed by Mary Reyland, CU Cancer Center investigator and professor in the Department of Craniofacial Biology, School of Dental Medicine. A total of 39 graduate students participate in the program, pushing the boundaries of cancer research using new and evolving techniques of study. Through a National Institute of Cancer (NCI) grant, the program also will have an integral role in training postdoctoral fellows who already have earned a Ph.D. and have obtained further training by working with a mentor.

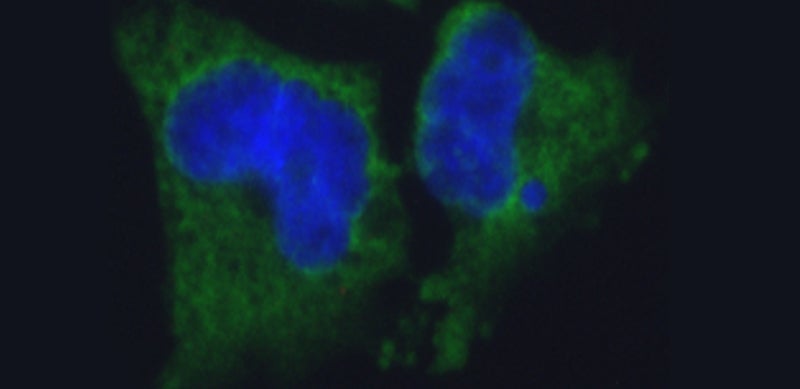

Beadnell has been studying the role of Src, an important protein that he said regulates growth, invasion and migration of cancer cells. In his work, he has been laying the groundwork for understanding how this protein effectively can be targeted in the clinic.

For students training in cancer biology, CU Anschutz is an excellent place to be, Reyland said.

“They are in an environment where they have a ton of access to the whole spectrum of research – basic, translational and clinical research,” she said. “That’s a huge benefit for people wanting to do disease-focused research like cancer.”

Beadnell agrees.

“The cancer biology program encompasses both the mechanistic and big picture/clinical aspects of research,” he said. “As it is often easy to get engrossed in the minute/mechanistic details of research, the close associations with the hospital and many medical doctors holding faculty positions within our program allow for an increased breadth of knowledge to provide clinical guidance and direction to our experiments.”

Because cancer biology includes multiple fields of study, Beadland said, it gives students a broad exposure to many different areas of study. For instance, the training program evolved from an experimental pathology program in 2005 and still offers a nod to its roots through a mini-course that provides an overview of pathology.

“We examine patient tumor samples under the microscope to gain a better understanding of tissue architecture and the pathology of cancer,” Beadland said.

Reyland became director of the training program in 2010.

“I’m passionate about high-quality graduate education and this was an opportunity to focus by passion in that direction,” she said.

The program, which places students in the research labs of participating faculty members who offer instruction and mentoring, has expanded and matured in the past six years and is considered a national leader in the interdisciplinary education of the next generation of cancer scientists.

As a testament to that fact, Reyland and co-principal investigator Scott Cramer, Cancer Center investigator and professor in the Department of Pharmacology, recently received word that the training program has been awarded a National Cancer Institute T32 grant, which will fund additional training positions.

Only a very few of these highly competitive grants are awarded, Reyland said. The T32 grant enables the program to recruit and fund the work of more trainees – especially postdoctoral trainees who are more advanced in their careers. The renewable, five-year grant will fund five postdoctoral trainees and one graduate student trainee each year.

“The people who get their graduate degrees often go and do different things, from science writing to working for a biotech company where they can be working on any number of things, including cancer-related projects, but sometimes not,” Cramer said. “People who are postdoc fellows likely are more committed to focusing cancer-related work specifically, and that is why the NCI puts an emphasis on postdoc training. The grant provides training for the people who are likely to be our next generation of cancer researchers who will crack this thing.”

The competitive positions are considered a prestigious opportunity for young researchers. They also are a resource for participating faculty, whose projects will benefit from an additional group member.

Cramer’s specialty is researching aggressive types of prostate cancer. He has recruited a postdoctoral trainee to work on a project that focuses on a cancer that accounts for as much as 40 percent of all lethal prostate cancers. “Her goal will be to develop a mouse model for this and to characterize the molecular pathways involved in it,” he said.

The T32 grant, Cramer said, also encourages and strengthens the interactions between more senior and more junior trainees.

“This makes for a more robust training program overall,” he said. “While some of this already occurs, the T32 more formally brings these two groups together.”