New study: Some asteroids live in own 'little worlds'

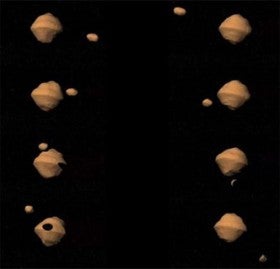

A new study indicates that some binary asteroids, like the pair depicted in orbit around each other in this visualization, have the ability to escape from each other shortly after they are formed.

Image courtesy JPL/NASAA new study indicates that some binary asteroids, like the pair depicted in orbit around each other in this visualization, have the ability to escape from each other shortly after they are formed.

While the common perception of asteroids is that they are giant rocks lumbering about in orbit, a new study shows they actually are constantly changing "little worlds" that can give birth to smaller asteroids that split off to start their own lives as they circle around the sun.

Astronomers have known that small asteroids get "spun up" to fast rotation rates by sunlight falling on them, much like propellers in the wind. The new results show when asteroids spin fast enough, they can undergo "rotational fission," splitting into two pieces which then begin orbiting each other. Such "binary asteroids" are fairly common in the solar system.

The new study, led by Petr Pravec of the Astronomical Institute in the Czech Republic and involving the University of Colorado at Boulder and 15 other institutions around the world, shows that many of these binary asteroids do not remain bound to each other but escape, forming two asteroids in orbit around the sun when there previously was just one. The study appears in the Aug. 26 issue of Nature.

The researchers studied 35 so-called "asteroid pairs," separate asteroids in orbit around the sun that have come close to each other at some point in the past million years – usually within a few miles, or kilometers – at very low relative speeds. They measured the relative brightness of each asteroid pair, which correlates to its size, and determined the spin rates of the asteroid pairs using a technique known as photometry.

"It was clear to us then that just computing orbits of the paired asteroids was not sufficient to understand their origin," Pravec said. "We had to study the properties of the bodies. We used photometric techniques that allowed us to determine their rotation rates and study their relative sizes."

The research team showed that all of the asteroid pairs in the study had a specific relationship between the larger and smaller members, with the smallest one always less than 60 percent of the size of its companion asteroid. The measurement fits precisely with a theory developed in 2007 by study co-author and CU-Boulder aerospace engineering sciences Professor Daniel Scheeres.

Scheeres' theory predicts that if a binary asteroid forms by rotational fission, the two can only escape from each other if the smaller one is less than 60 percent of the size of the larger asteroid. When one of the asteroids in the pair is small enough, it can "make a break for it" and escape the orbital dance, essentially moving away to start its own "asteroid family," he said. During rotational fission, the asteroids separate gently from each other at relatively low velocities.

"This is perhaps the clearest observational evidence that asteroids aren't just large rocks in orbit about the sun that keep the same shape over time," Scheeres said. "Instead, they are little worlds that may be constantly changing as they grow older, sometimes giving birth to smaller asteroids that then start their own life in orbit around the sun."

While asteroid pairs were first discovered in 2008 by paper co-author David Vokrouhlicky of Charles University in Prague, their formation process remained a mystery prior to the new Nature study.

When the binary asteroid forms, the orbit of the two asteroids around each other is initially chaotic, Scheeres said.

"The smaller guy steals rotational energy from the bigger guy, causing the bigger guy to rotate more slowly and the size of the orbit of the two bodies to expand. If the second asteroid is small enough, there is enough excess energy for the pair to escape from each other and go into their own orbits around the sun."

Several telescopes around the world were used for the study, with the most thorough observations made with the 1-meter telescope at Wise Observatory in the Negev Desert in Israel and the Danish 1.54-meter telescope at La Silla, Chile.

"This study makes the clear connection between asteroids spinning up and breaking into pieces, showing that asteroids are not static, monolithic bodies," Vokrouhlicky said.

The asteroids that populate the solar system are primarily concentrated in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter some 200 million miles from the sun, but extend all the way down into the inner solar system, which are known as the near-Earth asteroids. There are likely about a million asteroids larger than 0.6 mile, or 1 kilometer, in diameter orbiting the sun. Last month, NASA's WISE spacecraft spotted 25,000 never-before-seen asteroids in just six months.

Astronomers believe most asteroids are not solid chunks of rock, but rather piles of debris that come in shapes ranging from snowmen and dog bones to potatoes and bananas, with each asteroid essentially glued together by gravitational forces.

"Sunlight striking an asteroid less than 10 kilometers across can change its rotation over millions of years, a slow motion version of how a windmill reacts to the wind," said Scheeres, who has studied asteroids for the past decade. "This causes the smaller asteroid to rotate more rapidly until it can undergo rotational fission. It's not hard for these asteroid pairs to be pushed over the edge."

CU-Boulder doctoral student Seth Jacobson of CU-Boulder's astrophysical and planetary sciences department, a co-author on the Nature paper, said the most surprising part of the study was showing that sunlight played the key role in "birthing" asteroids.

"There was a time when most astronomers referred to asteroids as vermin," Jacobson said. "But the more we learn about them, the more exciting they are. They are not just big chunks of rock, but have the dynamic ability to evolve."

The asteroids in the study ranged from about 1 kilometer to about 10 kilometers or about 0.6 mile to 6 miles in diameter, said Jacobson, who added that one of the biggest questions is what lies beneath the surfaces of asteroids. "This is something we just don't know yet."

Asteroids have become a hot topic, Scheeres said. The Japanese spacecraft Hayabusa made two landings on the asteroid Itokawa in 2005 before its recent return to Earth – the first spacecraft ever to visit an asteroid and return to the planet. Scientists are hopeful the spacecraft recovered at least some particles from the asteroid, which may give them more information about the origin and evolution of the solar system roughly 4.6 billion years ago.

Other co-authors of the study are from institutions in North Carolina, California, Massachusetts, Chile, Israel, Slovakia, the Ukraine, Spain and France.