Five questions for Peter deLeon

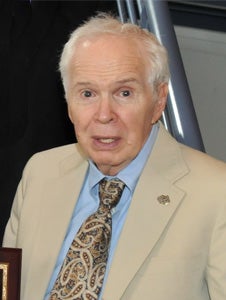

Peter deLeon is a soft-spoken man who is passionate about public policy analytics but whose political activism ended with the Vietnam War protests. A national and international leader in public policy research, he has been a University of Colorado faculty member since 1986. A professor of public policy at the School of Public Affairs at CU Denver, he recently was given the honor of Distinguished Professor.

“I was more flattered than anything else because it’s a distinction voted on you by your peers,” he says. “To be so honored is beyond anything I ever conceptualized. I always thought I was an OK scholar, but I would never have dreamed I affected my field in the ways that a distinguished scholar does. Other people feel to the contrary.”

He worked for the RAND Corporation – a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and decision-making through research and analysis – and received his Ph.D. at the Frederick S. Pardee RAND Graduate School. For a time, he taught at Columbia University in New York City. When he received an offer to teach in Colorado, he packed his bags.

DeLeon credits his wife Linda – who retired as an associate professor and associate dean of the School of Public Affairs -- for being his muse. He has skied since high school and played tennis on an NCAA championship team. (Some of his college teammates later captured Wimbledon.) He loves anything having to do with good food – cooking, dining or just plain worshiping. “We have eaten pretty much around the world and I have never really suffered from it,” he quips.

1. Your research topics include policy process, which is quite timely now and I assume always has been. Can the United States have a more effective process? Can the people be more involved?

Actually, policy research didn’t really begin seriously until the early 1950s. My success is predicated on the success of policy theories making inroads into the academy and the world of policy practice. The heritage of policy studies is easily coincident with my lifespan.

In a sense, we must recognize that policy in a university setting doesn’t always coincide in a practical setting. At the university, we talk more about policy theory and how theories create problems in perspective. President Obama and the speaker of the House and Senate president are engaged in day-to-day tussles as they articulate and carry out policy that they favor. We can look at them with great disdain because they aren’t doing what we do and we sort of like what we’re doing. There’s a great divide in the policy research community on whether policy research should be engaged in policy actions or whether we should sit in our ivory towers. Some say we should be engaged, but others will tell you that our perspective of the “real” world is limited and therefore of limited insight. Both of those arguments hold a lot of truths.

My dean and I sort of tussle on whether initiatives on the Colorado Constitution are a good idea. He claims that involvement of the Colorado voter has caused more damage to the state than good. He’s not entirely wrong. I would still claim that it’s a cost we should be willing to incur for the luxury of having a democratic system. It’s a confounding issue.

2. This year, we’ve seen unrest in several countries that resulted in the toppling of ruling governments. Is this a natural evolution? Can democracy gain a foothold in these countries?

It’s a hard question. I’m on the record as being a democratic theorist, but late at night, when I’m sitting with Jack Daniel’s, Jack and I really worry about this. Let’s take Egypt. One of the things that former president Hosni Mubarak did, for his own reasons, was reach a settlement with Israel that was not well thought of in Egypt writ large. With him gone, there are new tensions developing with Israel, so democracy per se is a double-edged sword. We simply don’t know enough in that situation as to look with great discernment and clarity as to what might happen. We don’t even have to go to Egypt. Look at it in terms of the Republican Party here in the U.S., which is on the horns of a Tea Party dilemma. I would claim that the Tea Party is not a problem in democratic society, since they’re only 20 percent of the GOP, but, in many legislative situations, they are a controlling 20 percent.

3. What is your teaching philosophy and what do you hope students take away from your classes?

I want them to appreciate the complexity of the issues. Someone might ask, “What is the confusion about immigration? They settle and do the best they can.” But that sort of posture is not well thought out; you must appreciate the nuances out there from both camps. Truth be known, migrant workers help keep the economy from going crazy because they work for depressed wages.

I want to encourage students to recognize that there are many sides to many issues. To talk intelligently about them, you have to appreciate what those sides look like and how they affect one another and to accommodate different views and different postures.

I particularly enjoy working with my students because they introduce me to new concepts I have never thought of before. So I stand to learn more from my students than they do from me. From me, they learn how to structure and analyze, but from them, I learn all sorts of new things.

4. What other research have you done that you are particularly proud of and what was the outcome?

One of my research areas at RAND was to better train U.S. fighter pilots for the Air Force. It was done through analytics looking at the training regimens and the constraints placed on pilots. The idea was to improve both so a pilot could be more skilled. Large amounts of research say that the more time a pilot spends in the cockpit, the better, so some air forces will have pilots spend their entire tour in the cockpit rather than just two or three years. But there are pros and cons to that. I made my arguments to the U.S. Air Force and was successful in changing the training regimen for fighter pilots.

5. Explain the “voluntary environmental program,” which is another area of interest for you.

Historically, most regulatory policy has been passed down by the state or federal government, saying, for instance, that you have to reduce the amount of carbon emissions by a certain percentage. The problem with this so-called command and control policy is that it wasn’t very effective. Companies would find ways around these control issues and the environment was getting worse in terms of pollution. Somebody came up with idea for a voluntary environmental program, where companies are told they have to get down to a certain level of pollutants or emissions but the “how” of doing that was left to the companies. There was some evidence that this was working.

A colleague from George Washington University and I looked at the ski industry, which had an environmental program that was voluntary. We wrote two papers, and the thrust of both was that the ski resorts that had accepted the voluntary program had worse results than ski areas that chose not to accept it, but the former benefited greater by claiming they were environmentally sensitive. Our argument was that these ski resorts were engaged in what we called green washing. That hit a popular chord, and led to coverage in The Denver Post, The New York Times and National Public Radio.