Taking on stereotype threat in the classroom

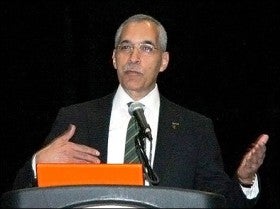

Claude Steele, Ph.D., provided the keynote address at last week's CU Diversity Summit.

Photo by Tom HuttonClaude Steele, Ph.D., provided the keynote address at last week's CU Diversity Summit.

Which sounds more daunting: completing an IQ test, or solving a puzzle? Most would say it's the former. And it's that kind of thinking that, indeed, causes more people to struggle with the IQ test rather than the puzzle – even if the test question and puzzle are identical problems.

That piece of research was among many illustrations shared by Claude Steele, Ph.D., during the University of Colorado's 2011 Diversity Summit. Titled "Elevating Learning Through Inclusive Teaching," the Feb. 4 event at Berger Hall on the University of Colorado Colorado Springs campus drew about 150 people from throughout the system, and featured a keynote address by Steele, provost of Columbia University and author of "Whistling Vivaldi: And Other Clues to How Stereotypes Affect Us" (2010, W.W. Norton and Co.).

A social psychologist, Steele's research has included examinations of why stereotype threat – when a negative stereotype about one's social identity is applicable to a situation – has an effect on academic performance, and how it can be changed.

For instance, he compared test scores in math for men and women; in one case, the women's scores ranked lower than the men's, apparently reflecting the stereotype about women being less capable than men at math and science. But when women about to take the same test were told, "This is a test where men and women perform equally," women's scores were virtually identical to men's. Similar research also showed leveling of otherwise disparate test scores between groups of ethnic minorities and whites.

There are ways to achieve similar results in everyday educating, Steele said. For instance, when giving feedback to members of groups affected by negative stereotypes of intellectual performance, "Make things challenging, but affirm their ability to meet these challenges." Constant, unconditional praise doesn't help, but telling someone that the work is difficult – and doable – does help.

Critical mass of ethnic minorities and women in an academic setting is crucial, too, Steele said. He spoke of Sandra Day O'Connor's great relief upon the arrival of Ruth Bader Ginsburg on the U.S. Supreme Court.

"A setting needs to have some sense of diversity, a sense that it's not bound to a single identity or minority group," Steele said.

He also stressed the need for role models and existence proofs – the highest profile example being President Obama. The more that minority students hear from others who succeeded in higher education, the more likely they are to succeed, too.

"Our students also need to hear that … intellectual ability is something that's incremental," Steele said. "The brain can expand."

The summit – organized by Kee Warner, associate vice chancellor for diversity and inclusiveness at UCCS – opened with welcoming remarks from CU President Bruce D. Benson and UCCS Chancellor Pam Shockley-Zalabak. Presentations on diversity-related efforts were provided by representatives of all four campuses: Alphonse Keasley, CU-Boulder; Paritosh Kaul, Anschutz Medical Campus; Philip Joseph and Janet Lopez, CU Denver; and Abby Ferber, UCCS.

Ferber described how she's using distance-teaching technology – real-time, high-definition video feeds – to partner with an African-American instructor in Rhode Island to team-teach a course on race and ethnicity. This helps the classroom move toward the critical mass that Steele spoke of.

"We really need to start thinking of the new opportunities that technology provides us," Ferber said.