In highly anticipated Shakespeare exhibit, the book’s the thing

When a Shakespeare First Folio is put on display at CU-Boulder in 2016, it will be surrounded by all the hoopla and excitement that one of the most valuable books in English literature commands.

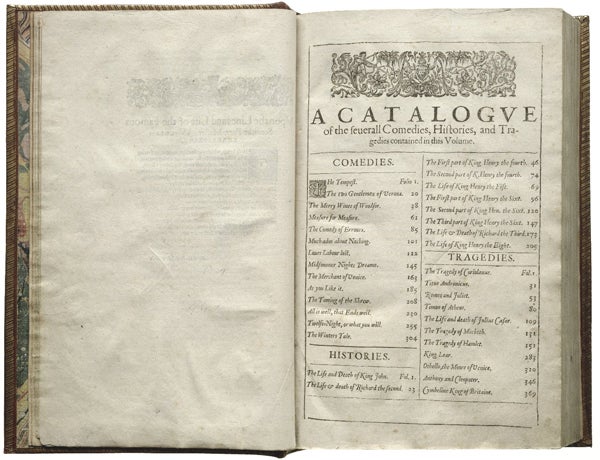

First Folios, which are collections of 36 of William Shakespeare’s plays, were printed in 1623. Eighty-two of the volumes are in the possession of the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C., and a few of those will tour the United States next year in recognition of the 400th anniversary of the Bard’s death.

At CU-Boulder, 10 colleagues spent months preparing an application to host the traveling exhibit, “First Folio! The Book That Gave Us Shakespeare.” Only one location in each state won the honor to display a First Folio. One of the conditions of participation was that the monthlong event would engage the larger community, a task that CU has happily embraced.

“It was really just a matter of gathering colleagues together to sit down and the ideas just kept coming and coming. It’s a great group and we were all on the same wavelength,” says Deborah Hollis, associate professor and the associate faculty director of Special Collections, who is a member of the committee that prepared the winning application.

It is believed that about 750 First Folios were printed, and just over 230 copies are believed to be in existence. (One recently was discovered in a small library in France where it had been mistaken for an 18th century edition.) That’s one of the reasons why a First Folio – on the off chance that it is up for sale – can go for $6 million and more.

While the rarity of the volume causes hearts to race, it is the magic and mystery of Shakespeare that has kept him alive throughout the centuries.

“Shakespeare tells important and timeless stories. They weren’t original stories; he got them from English history or some other prior works,” says Katherine Eggert, associate professor of English and the director of the Center for British and Irish Studies, who also served on the application committee. “What makes Shakespeare’s work great is the language that creates character. We remember his characters because they are so complex, and the reason they are so complex is because of the way they talk.”

It’s a complexity that other writers throughout history have tried to match. Eggert says Shakespeare paved the way for today’s novels.

Shakespeare was born in 1564 in Stratford-upon-Avon, England, likely on or near April 23. He wrote his first play between 1589 and 1591, and his last around 1613. When he died on April 23, 1616, at the age of 52, only a few of his works had been printed in small editions called quartos.

Seven years after his death, friends and colleagues from his theater company – Kings Men – compiled nearly all of his plays into a collection that became the First Folio. Without the publication of the book, says Eggert, it is likely that 18 of his plays would never have been known to the modern world. The First Folio “cemented Shakespeare’s reputation as not just a good playwright, but as a great author.”

Through the years, Shakespeare has survived a variety of attacks. Critics questioned whether his pedigree was adequate enough to actually have produced the works, some of which are considered the finest ever written in English. Later editors removed what they considered to be the “naughty” parts of the plays, says Hollis, and others have re-crafted pieces of the works to reflect the scholarship of the time.

Sometimes, changes to the plays were simply a matter of interpretation. In one instance, says Eggert, one section of a play is written in iambic pentameter – clearly indicating that it was poetry – but the volume shows the language as prose, printed in paragraph form. Editors along the way also have added stage instructions and lists of characters.

Individual First Folios also show variations because some books were proofed while others were being printed. Later editions, specifically the Third and Fourth folios, also contain plays that likely were not written by Shakespeare.

While the First Folio will be the star of the show at CU-Boulder, the university has planned numerous companion exhibits and events to “offer the public a lot of great opportunities to discover Shakespeare,” says Hollis.

The First Folio will be displayed at the CU Art Museum. Alongside the tome will be other rare books, including a Shakespeare Fourth Folio (published in 1685), which the university acquired in 1982 from a Denver bookseller. In order to give visitors a sense of Shakespeare’s world, a Mercator atlas from the 1600s and a Holinshed ‘s Chronicles (a history of Britain) – both from the university’s collection – also will be part of the display. Shakespeare likely used Holinshed’s writing as source material for “Macbeth.”

The university has requested that it be allowed to host the First Folio exhibit in August, to coincide with the season’s final performances of the annual Colorado Shakespeare Festival. Plans also include other Shakespeare performances around campus, numerous lectures, and outreach programs geared toward K-12 students. CU also hopes to set up a letter press outside Norlin Library to give the public a look at how the First Folio was printed then bound.

CU also has partnered with other organizations along the Front Range to plan concurrent activities. Denver Botanic Gardens will conduct botanic illustration classes, focusing on the plants in Shakespeare’s plays; Denver Art Museum will host a satellite exhibit of The Berger Collection, which features many artists from the period; and Colorado State University will concentrate on textiles of the time.

Hollis said committee members still are considering other ways to share the campus’s love of Shakespeare with the broader community. Because they want to focus on young students, organizers are seeking funding that would allow CU students to design and develop educational materials, including lesson plans, for teachers. Another idea is to get students to perform Shakespeare via Twitter.

The Folger plans to announce exhibit dates in April and CU will begin firming up events soon afterward.

“What I personally love about looking at a book like the First Folio or any important first edition of Renaissance literature is that it’s a way of touching the past,” Eggert says. “We’re looking at a book that has survived for 400 years and has had hands on it for 400 years and that somebody bought and had bound and gave to their descendants or sold to somebody who cared for it.”