Five questions for Tom Napierkowski

In the General Prologue to “The Canterbury Tales,” Geoffrey Chaucer says of the Clerk of Oxenford, “And gladly would he learn and gladly teach.” It’s a line that Tom Napierkowski says is “central to my identity. I want to continue to be a learner and I love teaching.” Chaucer has greatly influenced Napierkowski, so much so that at times he takes on the persona of the man considered the greatest English poet of the Middle Ages.

The professor in the Department of English at the College of Letters, Arts and Sciences has just finished his 40th year of teaching at the University of Colorado Colorado Springs – he earned his master’s and doctoral degrees at CU-Boulder – and along with his interest in Chaucer, specializes in minority and immigrant American literature and the history of the English language.

His classical high school education – four years of Latin, three years of Greek, two years of modern language – prepared him to be a philologist, and he saw literature as the logical next step. But once at Boulder, he says, “I fell under the influence of medievalists Harold Kane, Don Baker and J.D.A. Ogilvy. They were marvelous scholars and I fell under their spell and the joy of medieval literature.”

Napierkowski recently received the Distinguished Service Award for his years as a faculty member and for serving on the Faculty Senate Committee on Privilege and Tenure (20 years) and four terms as president of the UCCS Faculty Senate and Faculty Assembly. He also has spent 15 years working with the UCCS Educational Policy and University Standards Committee.

Outside of his research interests, he admits to enjoying historical fiction. “But I have high standards. Authors can’t take history and run off with it. Historical figures should be in the background, and an author can’t write in attitudes or actions or speeches for which there is no historical basis. And I love reading literary criticism when the critic is helping me appreciate the work I’m studying.”

Once he had an ambition to climb all of the state’s 14ers. “A few of them require technical climbing, and at no age has that seemed particularly attractive to me. At the age I am now, it seems particularly unattractive.” He says Mount Elbert is one of his favorite climbs. “It was a great climb in the early fall; the trees were beautiful. There’s something special about being above timberline, looking over the beauty of the state. It’s pretty spectacular.” Now he’ll likely climb a few more 13ers and continue a favorite winter activity – snowshoeing.

1. What prompted your studies of Polish American literature and what have you learned?

I grew up in a predominately immigrant Polish American neighborhood on the south side of Chicago. While I was a grad student in Boulder, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated and the English Department wanted to put together a course in African American literature. We had one prominent African-American scholar and no African-American students in the program. The faculty organizing the effort asked a few of us from the inner city if we would be interested in putting together and teaching courses on African-American literature. I was thrilled to accept. That experience led me to explore and become more knowledgeable about immigrant literature, especially Polish-American literature.

During the period of mass immigration (about 1890-1920), millions of people came here from eastern and southern Europe. This was a migration categorized as one “for bread.” The immigrants had a hard time making a living in Europe and many were escaping political oppression. They primarily were of peasant status, and the assumption made for many years was that these were people just trying to adjust. They were seen as, at best, semi-literate. As it turns out, these people had an enormous appetite for literature – fiction, poetry, theater – and they produced a wealth of it, some lost in backrooms. People like my grandfather and grandmother had voracious appetites for literature penned by fellow immigrants. I’ve been involved in efforts to entice some scholars from Eastern Europe to help discover, preserve and evaluate this type of literature. Without an appreciation of what these immigrants wrote, we will never really understand them. One can look at census reports and ship manifestos, but if we really want to climb into their souls, we need to look at their literature.

2. You visited Romania as a Fulbright Specialist. What did you accomplish there and what did you gain from the appointment?

I didn’t want to seek an appointment that would fill up a whole semester or whole year; the Fulbright Specialist Program provides the opportunity to go abroad for two to six weeks, depending on the needs of the host institution. I’d like to think I was a good ambassador for the U.S. in a part of the world where Americans aren’t regularly encountered. I hope that I brought to my students some sense of how English as a second language can be profitably approached. The students are enthusiastic but they don’t have language labs and their approach to improving their language skills is a bit different. I gave a few lectures on Middle English, Chaucer and African-American literature, and I think that I further excited their interest in learning.

3. You recently were recognized with the Distinguished Service Award. What are some of the achievements you’ve made of which you are most proud?

First, I’ve always tried to prevent faculty governance from slipping into a crisis organization. I’ve worked to keep the dialogue open and cooperated with the administration to achieve certain goals and to avoid what could have become crisis situations.

For a great many years, I was on the Privilege and Tenure Committee, which is, in essence, the in-house grievance committee for the CU system. On the many cases with which I’ve been involved, I have worked to resolve grievances equitably from both the faculty’s and administration’s perspective.

I’ve been involved for many years in the review of the status of non-tenure-track faculty. One of the big changes we’ve seen in higher education in this country is the higher percentage of courses taught by non-tenure-track faculty. Sometimes, these faculty members were treated as second-class citizens, and I’d like to think I have helped to gain a better appreciation and standing for them.

I really believe that when it comes to faculty responsibilities, it’s use it or lose it. Nature hates a vacuum. If faculty members don’t get involved in those parts of academic life that naturally fall to them, then others will take over. The faculty needs to be heard.

4. How have the university and/or teaching changed since you’ve been at UCCS?

When I came to UCCS in 1973, there was a dirt road to campus and the old sanitarium that had been changed into a university. Now we’re a significant regional, national, and even international university. We’ve grown in numbers of students and size of faculty. And we have more programs. But there’s some nostalgia, too. In 1973, the only thing that brought people down that dirt road to this emerging campus was their desire to get an education. There were no bells and whistles. We didn’t even have a cafeteria, only a few coin machines where one could get a Coca-Cola. That desire for education was inspirational.

5. Do you have a favorite item or artifact in your office?

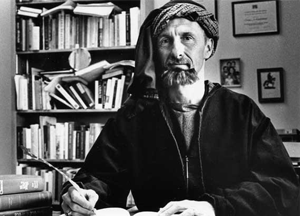

I’ve been in that office for 40 years, so I have lots of little artifacts that have special meaning, but I’ll choose two. One is a photo of me with Lech Walesa, who led the Solidarity movement in Poland. The other is a photo of Chaucer. You might say that is impossible. But several years ago, the Colorado Endowment for the Humanities put together a program of VIPs. We were invited to apply for support for Chautauqua performances, and I applied to be Chaucer. My grant was accepted and from time to time I give performances as Chaucer. So the photo is Geoffrey Chaucer, alias Tom Napierkowski.

It has special meaning because it is a chance to identify with Chaucer. He’s a comic poet in two important and different ways. He genuinely likes to make people laugh. But he’s also a comic poet in that he had a metaphysical, philosophical and theological view of the world that is positive despite the fact he lived through incredibly trying times. Partly under his influence, I share that comic view of the world.

One of the skills that Chaucer is remarkable at in his literature is characterization. His Canterbury pilgrims are a wonderful cross-section of medieval society. I tell my students that I have met all of those pilgrims. Not that I’m 600 years old, but because they still walk the streets of the modern world.

“Being” Chaucer is great fun. One performs for 40 minutes as the person. Then there are 10 minutes of questions from the audience to that person, and finally, in the last 10 minutes, one comes out of character. At one performance, after I had ripped off my little goatee and was speaking as Tom Napierkowski to the attendees, one of the ladies said, “My grandson is doing a dissertation on you …”