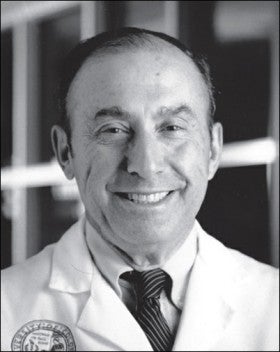

Five Questions for Henry Claman

Henry Claman, M.D., was no stranger to medical science or art: His parents were physicians in New York City and the family took great interest in the cultural opportunities they found there.

So his melding of the two interests comes as no surprise.

Claman is recognized as a leader in the field of immunology, where his research led to a groundbreaking discovery, but he also understands and promotes the importance of intertwining art and literature into a medical curriculum so that doctors are better able to observe and empathize with their patients.

He has spent 50 years at the University of Colorado, where he served as head of the division of allergy and immunology for 25 years. Now semi-retired, he is a Distinguished Professor at the School of Medicine and serves as associate director of the Arts and Humanities in Health Care Program.

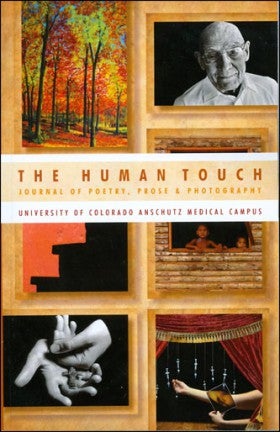

For the past three years, the program has published "The Human Touch," a literary and arts anthology. The fourth issue has a spring 2011 release date. The book contains prose, poems and photographs from those involved with the Anschutz Medical Campus.

— Cynthia Pasquale

1. You have taught and practiced at the University of Colorado for many years. Why did you choose this avenue rather than private practice?

I had planned to go into the practice of internal medicine and at the time I was required by "the Berry Plan" to spend two years in the U.S. Army. My hospital commander asked me (ordered me) to develop an allergy clinic in his hospital. I refused. But the third time he asked me, in his very nice way, I complied. So with minimal training, I was director of an allergy clinic. What I did not tell him was that my mother was a prominent practicing allergist in New York City.

I did this for two years, sort of on-the-job training, and found it quite fascinating, especially with the exciting developments in immunology going on in the 1960s. I was still planning to go into private practice in St. Louis, but I had a lingering question in my mind whether research might be a better avenue for me. I decided to take a fellowship in immunology and chose the University of Colorado because it had an outstanding program in immunology and allergy under Dr. David Talmage.

I started to work in the lab, and although all my experiments failed, I was having a wonderful time. I ended up combining teaching, basic research and a clinic practice as an allergist and stayed here because I liked what I was doing.

2. How did you become interested in art and why is it important to integrate art and medicine?

I was born and raised eight blocks from the front door of the Metropolitan Museum. I used to go there when it was practically empty and free. My family was interested in museums, concerts, theater and ballet, and New York was a wonderful place for those sorts of things. I don't have any artistic talent, but art and music mean a great deal to me.

When I experience something that means a lot to me, my personal rewards are both emotional and intellectual; I want to understand what it's all about. It would be a gray, silent, depressing world for me without art and music.

The idea of integrating art and medicine started out when a second-year medical student read an article in JAMA (Journal of the American Medical Association) about Yale's dermatology department, which had developed a program to sharpen medical students' observational skills by training them to look at art. Then those skills were translated into the skill of describing dermatologic lesions in patients.

As an educator, I decided to try this using PowerPoint slides. And that broadened into the medical humanities program, which emphasizes the human side of medical theory and practice.

We still hear stories of physicians and other health-care workers who are good at science but not so good at person-to-person interaction, which is unfortunate. Our program is not the only thing in medical school curriculums that emphasizes the humanistic side of medical care. There are some wonderful pictures and short stories, novels and art that show the human side of pain, suffering, comfort and care. And that's what the Arts and Humanities in Health Care Program does.

3. What does the Arts and Humanities in Health Care Program entail? How does "The Human Touch" fit in?We have half a day for first-year med students, improving their observational skills using art. We publish "The Human Touch," we have an elective in arts and literature, and a film series that is directed by Howie Movshovitz (director of film education at the College of Arts and Media at UC Denver) and Tess Jones (associate professor in the department of internal medicine and director of the Arts and Humanities in Health Care Program). We introduced an exercise in reflective writing for third-year med students in which they write about an experience they had with patients, a nurse, a patient's family or the health-care system, and what went well or what didn't go well.

It's not about the science of it, but how they feel about it, like Anton Chekhov, who was a physician and a writer. The work must be handed in and it usually is discussed in small groups, but the pieces are not graded. A number of these make their way into "The Human Touch" and Colorado Medicine, the bimonthly magazine of the Colorado Medical Society. Some of them bring tears to your eyes; some of them make you angry as hell.

A medical center anthology had been published before, through the department of psychology by Dr. Richard Martinez, but it failed to thrive. I picked up the idea, gave the anthology a new name and a new format, and talked some medical students into being the editors. "The Human Touch" is distributed free thanks to the support of the dean's and chancellor's offices.

"The Human Touch" is juried anonymously and there is a move to put it online. Another part of the program is a special section in the Health Sciences Library, the Drs. Henry and Janet Claman Medical Humanities Collection, which contains books and DVDs on the subject.

(Submissions to "The Human Touch" anthology are welcomed from students, faculty, staff and friends. Guidelines for submission are on page 166 of the current edition, which is available free at the front desk of the Anschutz Medical Campus Bookstore, Building 500. The deadline for submissions is Jan. 17, 2011; they should be sent tothehumantouchjournal@gmail.com. The editor in chief is Christina Crumpecker.)

4. What would you consider your biggest accomplishment?

I was given credit for an important scientific discovery based on experiments we did in the 1960s. We were the first people to show the interaction between two lymphocytes, the T-cells and B-cells, and how they formed the antibodies that give us immunity from infectious diseases. The discovery changed the direction of modern cellular immunology and explained many findings in a new light and unraveled the great complexity of the immune system. Many years later, it has direct implications for understanding diseases such as AIDS and the development of newer therapeutic and diagnostic agents. We had no idea how important it was then.

5. Your love of art translated into a book, "Jewish Images in the Christian Church: Art as the Mirror of the Jewish-Christian Conflict, 200-1250 CE." How did you decide on the topic?

My wife, Janet, and I are very fond of medieval art. We were in the museum of the Duomo of Milan, looking at the statues, some of which had been on the roof for hundreds of years.

My wife said, wait a minute, this is a Catholic church, but there are statues of Abraham, Moses and Elijah. Why? So I said I would find out why.

The book is a crash course in medieval art, and shows that by looking at this art very carefully, you can learn how Christianity dealt with Judaism in general and the Hebrew Bible in particular. The early Christian Church was faced with questions about what to do with the Hebrew Bible and decided to keep it and reinterpret it in the Christian framework. The book discusses how that was done and, over the centuries, the changing Christian attitude of Judaism through art.

I gave lectures on the idea and the book came out of those lectures. These interpretations of Jewish biblical events had been done before; I organized and illustrated them. The writing and organizing of the book was fun; getting a publisher was not.

Want to suggest a faculty or staff member for Five Questions? Please e-mail Jay.Dedrick@cu.edu