Five questions for Carol Runyan

Injury is the leading cause of death for people ages 1 to 45, and has been called the last great plague in America. Because so many youth are affected, injury (including violence) is responsible for more years of potential life lost than heart disease and cancer combined.

But because injuries traditionally have not been addressed fully as part of the public health domain, funding for injury prevention research has been limited.

Carol Runyan is working to change that. She has spent more than 30 years in the injury prevention field and recently was awarded the 2014 Distinguished Career Award from the American Public Health Association’s Injury Control and Emergency Health Services (ICEHS) Section. In 2012, she received recognition from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as one of the most influential leaders in the field over the past 20 years.

A professor of epidemiology and of community and behavioral health at the Colorado School of Public Health, Runyan also is a professor of pediatrics at the CU School of Medicine on the CU Anschutz Medical Campus and directs Colorado’s Pediatric Injury Prevention, Education and Research (PIPER) program, a collaboration of the schools of public health and medicine and Children’s Hospital Colorado.

Early in her career, Runyan was interested in both social and biological sciences and the field of public health seemed to be a perfect match for her. She also was interested in adolescent health – including injury. A summer course she took in 1980 sealed the deal.

“I was immediately taken by the clarity of how the field is conceptualized and how the approaches used in injury prevention exemplify classic approaches in public health,” she said. Drawn to topics and issues out of the mainstream, Runyan found that the field of injury prevention provided her with the opportunity to develop an agenda and push it forward.

When she came to CU from the University of North Carolina in 2011, she began to find people working in or interested in injury prevention and helped bring them together. “One of the things I’ve been trying hard to do is help people connect with each other so that we can build a network of people with the idea that the whole is greater than sum of parts.” Part of her job, she said, is being a matchmaker and putting together people with people and people with ideas.

“We have the capacity at this institution to provide major leadership throughout our region as well as nationally if we can get over the hump with respect to funding, and get a set of cohesive programs launched. We have the capacity to move the needle if we can marshal the necessary resources.”

1. You said that approaches used in injury prevention exemplify classic approaches in public health. What do you mean by that and why hasn’t injury prevention received more attention until recently?

The field of public health had a tradition of focusing on the context in which health problems occur. Current trends have focused on individuals and what people can do to make themselves healthier. While there are important things that people need to do to stay healthy, there’s a tendency to basically place blame on people for their illnesses, when in fact, a classic public heath approach would say that the environment has a lot to do not only directly with health, but also with what people are able to do to affect their own health.

For example, it’s not just about whether people exercise enough, but whether they have safe places where they can exercise. It’s not just about whether people wear seat belts when driving, but also about making sure that cars and roads are safe so that not all of the safety burden is placed on individuals.

My master’s program in public health was focused on thinking in those broader terms and understanding the health and safety of the environment. My research is mostly based on finding solutions at the environmental and policy level – thinking of public health as a process of social and system change.

There are several reasons why injury prevention has historically received less attention. One is that we have had a linguistic problem of referring to injuries as “accidents,” which conveys a sense that things just happen. In fact, the word “accident” has been banned from some professional journals. I start teaching about injury by saying that if students have that perspective – that they assume it’s fate or chance – then they might as well forget about taking the class. Public health is all about making change.

Another issue is that injuries are a hugely broad set of problems, and while there are many similarities across different types, it is often easier to assume that fixing the problem is someone else’s responsibility – another agency or organization -- for example. Traffic safety, for instance, is a problem of the transportation department, or worker safety is a labor problem, and that way no one has to own the entire set of problems.

I keep trying to figure out why this isn’t true for cancer. There are lots of different types of cancers and different approaches, but somehow they are more unified. We have to figure out how to do that with injury prevention.

Because it has been so fragmented and not part of the public health domain until recently, injury prevention wasn’t addressed broadly by federal agencies until the 1980s. There is no National Institutes of Health agency dedicated to the problem, partly because injury doesn’t fit so neatly in the medical model. It wasn’t until 1985 that funding was appropriated by Congress to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to start an injury program. Even so, the field is very poorly funded, receiving only a fraction of the money that goes to other health problems – completely out of proportion to the magnitude of the problem.

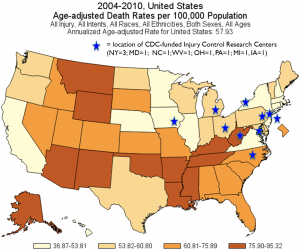

2004-10 US Age-adjusted Death Rates per 100,000 Population (click image for a larger version)

The CDC funds 10 research centers, but not a single one is west of Iowa, and statistics show that the highest injury fatality rates are in the West and South. (See graphic at right.)

Over the years, injury has become increasingly recognized as a legitimate part of public health, but it is still a long way from being seen as the important issue that it is. We need to design environments and products to assure safety and not rely on individuals to always know and do the safe thing. For example, we can teach parents and babysitters to test bath water to make sure a baby isn’t scalded, but wouldn’t it be better to make sure the water coming out of the tap doesn’t go above 120 degrees? We can do that by setting the temperature on water heaters at a safe level at the factory so that people don’t have to actively change anything unless they want to increase the temperature. For many safety matters, we shouldn’t have to rely on individual behavior, because humans make mistakes. Instead we should engineer the product to avoid human error as much as possible to allow the environment to be safe.

The same goes for guns. We’ve had the technology for close to 100 years to make guns so that a child can’t fire a handgun, so when a 3-year-old picks up a parent’s gun, they can’t shoot themselves or their little brother. But, we have failed to implement the technology – and, as a result, preventable deaths keep occurring.

2. Is there a subset of research that intrigues you most?

I’ve studied adolescent workers for about 15 to 20 years. It’s an area where there is needless injury and we need to figure out how to make work environments safer. I am currently designing new research to learn more about how employers approach training and supervision of young workers and where the gaps are in safety practices and adherence to labor laws.

Since coming to Colorado, I’ve been focusing some work on suicide prevention because it is such a huge problem here. We have one of the highest suicide rates in the country, and we need to solve it.

One example is our work on suicide prevention that is focused on using health care providers to counsel families to lock up medications and temporarily remove firearms from the home when someone is in crisis. We are completing a small project at Children’s Hospital Colorado that showed that both clinicians and parents of suicidal youth were very receptive to delivering and receiving these messages. We are now starting a regional study to see how other hospitals approach this issue.

We don’t know why Colorado has such a high suicide rate. But one of the factors is access to mental health and reducing the stigma related to mental health care. If you are in a crisis, you can’t wait for six months to receive services.

There also is a large proportion of suicides that occur with firearms. Colorado, like other states in the West, has a high ownership of firearms. National studies have shown that states with high gun ownership have higher suicide rates.

Another source of suicide in our state is prescription drug overdoses. With adolescents, it is sometimes hard to tell if it was a suicide or an unintentional poisoning with a prescription drug. It’s an issue nationally, as well, because prescription drug fatalities have surpassed motor vehicle deaths as a cause of death – a fact that is shocking to most people who have no idea how dangerous prescribed drugs can be.

3. How has your research/work influenced change?

I am proud of my work in a number of areas where I have gotten things started --- with others following up with the finishing touches. For example, I led development of a trial emergency department surveillance data system in North Carolina in the late 1980s. Though our system was never fully implemented, it laid the groundwork for development of national standards, and a very robust system was developed about a decade later by some colleagues. I did a major study on residential fires in the 1980s as well, leading to changes in North Carolina state policy to require smoke alarms in all residential properties. And, I have done research for a number of years on the experiences of young workers (under age 18), trying to bring to light the hazards they are exposed to and how they often are a forgotten part of the workforce. More recently, I tackled the question of whether colleges performing criminal background checks before admitting undergraduates could predict who will be engaged in misconduct on campus as a way of addressing campus violence (it doesn’t predict).

Some of my most gratifying work has been training others – both graduate students and practicing professionals in the principles of public health and injury control and watching them use that information to advance the field.

4. You founded PIPER when you came to CU. What is the mission of the program and what, specifically, are some accomplishments of the program?

Our mission is “To drive evidence-based practice through discovery, translation and workforce development.” As part of building the program, I was able to recruit staff and faculty to work with me to create a strong presence for injury prevention on this campus. I was fortunate to hire four very talented individuals and to engage with other scholars already on the campus. As I often say when I meet new people, ‘You may not know it yet, but you really are interested in injury prevention.’ It usually gets a laugh and some attention. Once people find out what injury prevention is all about, they often are more interested than they thought they were.

When people stop to think about it, they can usually think of a number of friends and family who have experienced serious or fatal injury. In fact, I ask students to draw their family tree and mark all their relatives who have experienced an injury resulting in death or medical care. Rarely is there someone who does not have at least a few family members to tell about. In my own family, for example, my grandmother died of burn injuries while several ancestors were murdered during the Holocaust, and several others (including me) have experienced less serious injuries -- resulting in sprains and fractures.

We have accomplished a lot in the three years we have been operating as a program. This includes nurturing relationships among interested individuals on campus who are gaining from working together and exchanging ideas as well as seeking and receiving funding for new projects. Our team is working on topics that range from falls in older adults to motor vehicle safety to sports injury to gang violence to dating violence to suicide to prescription drug abuse to poisoning by marijuana to occupational injury. We are engaging students in this work and connecting with lots of state and local agencies to help them achieve goals in injury prevention – and are learning a lot from their work.

5. You have had a distinguished career. What have been some of the highlights? What about the lowlights?

Highlights have been working with so many bright and eager students who bring both energy and ideas to the task of finding problems and solving them. Also, I have been very committed to bridging the research and practice worlds and to integrating my training in health behavior, policy and epidemiology. Sometimes that means that I am not as expert in anything as I might like, but I can do a bit more boundary spanning as a result.

The lowlights have centered on the fact that injury is still not recognized as a problem in a manner commensurate with its magnitude as a health issue, and the fact that funding is so meager. This is a perpetual problem and, as a result, it can be hard to recruit new talent and to stay positive. I think one of the challenges is convincing younger scholars that all of public health is about social change and that the process takes a long time. We need to take a long-term view and not just carve things up into tiny pieces because it is fundable.

I am unabashedly an idealist and have to remind myself sometimes to not get discouraged by the pace at which change happens. But I also try hard to encourage others to be more idealistic and to have high aspirations and push for more rapid pace of change.