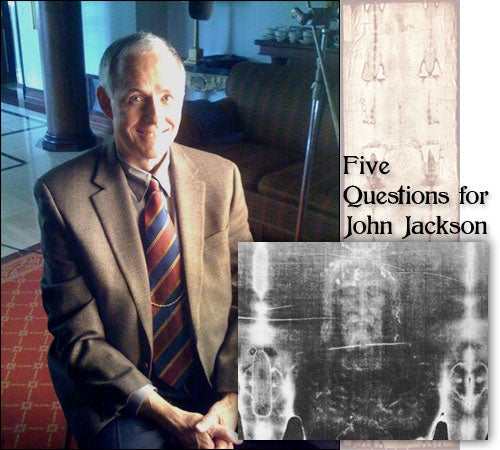

Five Questions for John Jackson

Wavelengths and atoms, Albert Einstein's theories and the space-time continuum occupy a majority of John Jackson's daily thoughts. He spreads his enthusiasm for science to the students in his modern physics class at the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs, where he is an honorarium instructor. Previously, he was a faculty member at the Air Force Academy. He earned his doctorate in physics from the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School and was a scientist at the Air Force Weapons Laboratory in Albuquerque, N.M.

But much of his renown has come from his research on the Shroud of Turin, a linen cloth bearing a negative image of a crucified man. Many believe the shroud is the burial fabric of Jesus. Jackson and his wife, Rebecca, direct the Shroud of Turin Center, a nonprofit dedicated to research and education.

In 1978, Jackson led a team of more than 30 scientists who conducted a series of tests on the cloth. The team found the image was not painted, dyed or stained, and that bloodstains on the cloth were real. But in 1988, radiocarbon tests dated the shroud to the 14th century, not the first. Jackson, however, believes those tests were inaccurate. He continues his research: "Shroud of Turin," an hourlong documentary that premiered in March 2008, details new efforts by Jackson and others. For more information on this film and another made in 1978, visit www.silentwitness2.com.

1. You've devoted much of your life to researching the Shroud of Turin. Are there upcoming publications in the works?

There are plans for a variety of papers. All of them are consistent with the burial cloth hypothesis.

Where I'm at with the shroud and radiocarbon dating is best expressed by the "Shroud of Turin" documentary, filmed by the BBC and in part at UCCS, which showed for the first time how the historical research, much of it developed using data we collected in 1978, contrasts with radiocarbon dating. I think the case can be made that there is a genuine disconnect between the shroud authenticity and radiocarbon dating. The work to be published shows the shroud existed in Constantinople and calls into question the dating. My hypothesis is that enriched carbon monoxide might have contaminated the shroud enough to move the date more than a millennium.

2. Last year, you approached Oxford University about testing your hypothesis concerning contamination. Where does the testing stand?

Professor Christopher Ramsey, the head of Oxford's radiocarbon accelerator unit, is interested in testing the hypothesis. (The lab was one of three that conducted the 1988 tests.) We still have a ways to go because we need to raise the necessary funding. It's difficult to do in this environment with the economy the way it is. And the perception (that followed) radiocarbon dating (that the shroud was an artistic forgery) doesn't help. We think we have credible approaches to the problem. We've got the road map and the car to get there; we just need the gasoline to go from point A to point B in our research.

3. Italian scientists say they have reproduced the shroud using red ochre and acid. Have you seen the scientists' methodology and do you have opinions on the work, which was funded by the Italian Committee for Checking Claims on the Paranormal and an organization of atheists and agnostics?

As far as we can determine, this hypothesis was released in the popular press, and hasn't undergone what I would consider serious peer review. Because it's not available in archival literature, we're limited as to how we can test this idea. While I'm not in the position to divert precious resources to try to test this, we can look at whether discoloring cloth with acid would be a possibility. We tested red ochre pigment and sulfuric acid. The ochre is there to guide the artist in applying the acid, which is what produces the image. But on the shroud, the blood images came first and the body image came afterward, according to our tests in 1978. It's just the opposite of what the Italians said. The body image in the Italian tests also doesn't have the same intensity as the one on the shroud. The shroud is a three-dimensional relief, while the Italian study produced only a binary image.

4. The Shroud of Turin will be displayed in April and May next year. It underwent some conservation in 2002. Does that concern you?

It's one thing to conserve the object; it's another thing to conserve the scientific information that was compromised by the conservation. It's gone from the shroud. Thankfully, we have some of that documented through our 1978 work; otherwise, the information would not be available for others.

The 2002 renovation did give us the ability to see the back side of the shroud. When we examined the shroud (for six days in 1978), I didn't want to authorize our team to do that because we hadn't thought through that process and I didn't want to damage the cloth. So the entire backing (that was sewn onto the shroud in 1534 after it was damaged by a fire) was taken off for the first time in 450 years. The back was photographed. I have the pictures right here in front of me.

5. Over the years, has your belief ever wavered that the Shroud of Turin was the cloth that covered Jesus in his tomb? What would it take for you to acknowledge the linen is not connected to Christ? Conversely, what would it take to prove beyond a doubt that the image shows Christ?

I am a devout Christian and my faith is very important to me. But I am also a scientist who spends most of my time trying to disprove hypotheses my colleagues and I think up, rather than find things that prove them. The last thing any scientist wants to do is publish something that is refuted.

I think we are looking at the actual burial cloth of Jesus. It's the only hypothesis that makes sense. It is not a work of the hand of man or a creation using some physical technique. But I have to hold up the possibility that something could change that hypothesis. I don't think science is ever going to be able to prove that it is the burial cloth. Science isn't wired that way. You have multiple hypotheses that stand up to competing hypotheses. (The theories) stand up as long as they stand up to testing. If you do this long enough, you end up with only one hypothesis. But how do you know when you've exhausted all possibilities?