Five questions for Tanaya Winder

Growing up on the Southern Ute reservation in Ignacio, Colorado, and as a member of the Duckwater Shoshone Tribe, Tanaya Winder believed that being successful meant becoming a doctor or lawyer, careers that mainstream society deemed worthy.

She was taught that living a successful life meant living not just for yourself, but also for your community. Back then she thought a medical or legal career was the way to do that.

And so she set out to be a lawyer and headed to Stanford University. But the university opened her eyes to other possibilities, including poetry. While at Stanford, she lost a friend to suicide.

“I was pushed to the brink with deep losses, and I started thinking about what actually makes me happy,” she said. “I asked myself: What I am passionate about? And, how can I use that passion to create a life that embodies my own definition of success – good representation and giving back, honoring my gifts, and also something that makes me happy?”

Her choice to be a poet, writer, artist and educator has served her – and many others – well.

In 2013, she became the director of the University of Colorado Boulder’s Upward Bound program, which supports high school students from disadvantaged backgrounds and prepares them for academic success, both in high school and beyond. While students are engaged in the program throughout the year, for six weeks each summer they live in a campus dormitory and attend classes in math, science, foreign language, composition and literature.

Winder’s first introduction to the program was during visits with her older sister who was enrolled in the Upward Bound program. She followed in her sister’s footsteps and was accepted into the Upward Bound program as a high school student. She returned as a resident adviser in 2007, and later worked as an instructor assistant, an instructor and a resident supervisor. In 2009, she became the assistant director of the program.

She earned a bachelor’s degree from Stanford and a master’s in creative writing from the University of New Mexico. She has taught writing courses at Stanford, CU Boulder and the University of New Mexico.

She said she loves being part of Upward Bound. “The program is for students, but you get so much, too. It helps you grow as a person.”

1. Why did you choose poetry as a means of expression and does your work have an overarching theme?

Poetry allows you to manipulate time. You can slow down and focus on the moment. There are so many things that happen to us in life and we focus on the big events – graduation, a marriage or the day somebody dies. We don’t always focus on a moment or a gesture somebody makes, like someone holding you or a hand reaching out. In poetry, you can take that moment and elevate it to have the significance of an event. It allows you to create mosaics and juxtapose things and place different events and experiences and moments against each other to create new meaning. I like being able to do those things.

The overarching theme of my writing is love in its different forms – romantic love, intimate love, community love, environmental love, social love, universal love, and how self-love ties into all of those forms. Love is medicine, a powerful force. In everything I do, I hope to teach revolutionary love; radical love; a phrase I call heartwork.

2. What are your duties as the director of the Upward Bound Program and what is your mission?

The program is funded to serve 103 students who come from eight different states and reservation communities. Two-thirds of the accepted applicants must be both low-income and first-generation students, and the other one-third can be either low-income or first-generation students.

As director, I am the captain of the ship, making sure everyone has what they need, including self-love. I offer advice and follow what’s happening in education – especially in Indian education – and what is happening in the communities we serve. All of these things affect how the students learn and how they interact in their schools. It’s important to know Native American graduation rates from high school diplomas to bachelor, master and Ph.D. degrees and knowing what high school students are up against and the choices they have when it comes to higher education. I also try to connect students with what they feel drawn to or connected to and figure out new ways to motivate them.

I ensure we adhere to grant requirements and I work with my dedicated staff to develop the curriculum for our summer institution. I hire the teachers and oversee the environment the students get to engage in. I try to make the summer sessions loving and fun where students can feel safe and protected, a space where they can dream and find their passions – sooner than some of us who took a different path and found those passions later in life.

There are so many negative stereotypes around Native Americans – alcoholism, diabetes, violence and things of that nature – and so as the 1 percent in the country, you might often be the first Native American some people meet. You then are basically representing not only your family and your community, but also all native people. The narrative people don’t always see is that we are a beautiful, strong and resilient people and it is important that you are living a life that contributes back. That’s part of our indigenous perspective – to think about the whole – the past (where we came from), the present (where we are now) and the future (where we are going).

What the country often forgets is that as Native Americans, we’re survivors of genocide. There was an American holocaust and people don’t realize that we are still dealing with the aftermath of that trauma and that ancestral memory passed down from being massacred and being put in boarding schools. Native Americans have a traumatic history of education, so how do we grow from that and dismantle the stereotypes and move forward using education to serve our purposes? Because of that history, like a lot of communities, Native American communities are struggling, whether it is depression, or high rates of suicide or domestic abuse and impoverished areas. That affects the students and how they are in their schools.

As with any student living in poverty, seeing your parents live paycheck-to-paycheck and focusing on month-to-month survival mode doesn’t give you the privilege of dreaming long-term. And so at Upward Bound we encourage dreaming. When the kids are here, they have three meals a day, a safe place to live, and they are taken care of. Of course, some students come from supportive and loving families, too. But if they don’t or if they must take care of siblings or have other responsibilities, when they are here they get the freedom to just be kids.

We admit them as rising sophomores and keep them for three years. We are a family. They get to know each other and the program creates a powerful networking system as well. A lot of our alumni are powerhouses in their tribes or in their communities, or they take on different professional positions throughout the country.

3. How do you keep the program innovative and how do you connect with and motivate the students?

A lot of schools don’t really incorporate Native American history into what they do. It’s not really taught a lot in history classes or history books. For instance, some of my friends who got their master’s degrees at prestigious institutions like Harvard found that Native Americans aren’t even included in the population breakdowns. That’s symbolic annihilation that makes us feel invisible. We constantly have to advocate for ourselves. So, at Upward Bound, we always make sure that we teach from a culturally based perspective, including the history of different tribes, and we discuss how to move forward as indigenous peoples. We teach them about options they have and prepare them for college experiences.

I think I motivate and connect with students by just being real and honest and not trying to be somebody I’m not. If I’m my real and authentic self, people in general and students connect to that. I like to remind them that they don’t just matter to me but they also matter to the world; they are necessary to making the world a better place. I try to motivate by being a mirror reflecting all the amazing things I see about who they are and all the potential they have.

I also feel that hiring good staff helps motivate the students. These are people who actually care about the students, not people who have a savior complex. Good teachers know that part of the work is empowering students to realize they are capable and able of “saving” themselves. I also try to walk my talk. I tell them they can do anything and pursue what they are passionate about, and so I try to live my life in that way, too.

4. You recently were honored with the 2016 National Center for American Indian Enterprise Development award as one of “40 under 40” emerging American Indian leaders who have made significant contributions to the community. What does the award mean to you?

I was excited about the award. I visualize myself as a connector who connects people to each other and to different opportunities. I’ve always been the kind of person that, if something doesn’t exist, I’ll make it or create that space.

The award came from several things. There are high rates of murdered or missing indigenous women and high rates of rape in the population. Along with several other Indigenous women (Hannabah Blue, Nanibah Chacon, Netha Cleoter), I co-created a traveling earring exhibit titled “Sing Our Rivers Red.” We collected more than 4,000 single earrings to raise awareness about the issue. It has now become two traveling exhibits and has taken on a life of its own.

After graduate school, I co-founded a literary magazine, “As/Us: A Space for Women of the World,” which focuses on writings by indigenous women and women of color. It’s been going strong for over four years and has an international readership. A fellow writer, Casandra Lopez, and I started it because we struggled to find places to publish and share our writing, and so we wanted to create a space where we could share work by other women of color writing powerful stories.

Most recently, I have been traveling around the country as a motivational speaker and doing performance poetry. I also created an indigenous management collective – Dream Warriors Management – where I am the manager for three Native American hip-hop artists (Frank Waln, Tall Paul, Mic Jordan) and one public speaker (Kelly Holmes). The collective helps us to support each other and talk through issues. We also have a small scholarship that encourages and helps a Native American high school senior study art. So the “40 under 40” award honors all of those parts of me.

5. Do you have hobbies or activities you enjoy outside of work hours?

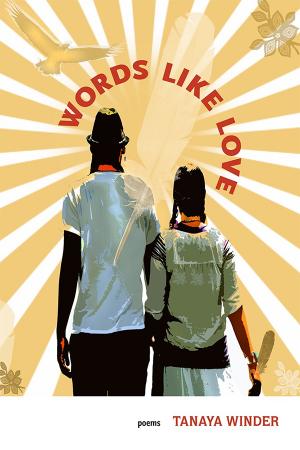

I’m always reading or writing. West End Press based in Albuquerque published my first book, “Words Like Love,” in September 2015. The book is now in its second print run. Now, I’m working on my second collection titled “Why Storms Are Named After People and Bullets Remain Nameless.” It doesn’t feel like work to me because it’s what I love to do. I also love to listen to music and I sing during some of my poetry performances, so I take singing lessons here at CU.

I get inspiration for my poetry from many places: If I see someone do something nice, or hear something sad on the news, or while traveling I hear people’s stories. When I’m working with students who are going through a hardship. I want to write something that I feel like they need to read, to help them feel they are less alone in the world. I write the book I need to read and I hope that that helps others find healing as well.