Five questions for Erin Tripp

Lichens — small but complex organisms — can grow nearly anywhere, but new species usually are found in hard-to-reach places far from urban areas. Yet Erin Tripp recently found two confirmed never-before-seen lichens at White Rocks Open Space, a short drive from Boulder. She also located two other specimens that might be new species.

Tripp, curator of botany at CU’s Museum of Natural History and an assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at CU-Boulder, discovered the new species at White Rocks while inventorying the lichens there.

She has been at CU for two and one-half years, coming to the university after doing post-doctoral work at the Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden in California for four years. Lichens, a combination of fungus and alga, aren’t her only specialty. She also studies the systematics (evolutionary relationships) and taxonomy of a large lineage of flowering plants (Ruellieae: Acanthaceae), composed of about 1,200 species. Two current research projects that she is pursuing are the evolution and speciation within a radiation of Acanthaceae (the genus Petalidium) in the ultra-arid ecosystems of Namibia, and lichen biodiversity and evolution in the southern Appalachian Mountains, particularly Great Smoky Mountains National Park, where she and a colleague have been working for nearly a decade.

“That’s life as a biologist — never short on projects or ideas but only short on time and, on occasion, funding. You know you have found the right career when you love your job so much that it doesn’t feel like work. If I weren’t a professional biologist, I would be doing it in my free time,” Tripp said. “I don’t understand how our species can be anything other than completely fascinated and baffled by the natural world that surrounds us. There is so much to learn, so much more than can be achieved in any person’s lifetime, which is what makes ‘the science of life’ simply the best subject on Earth.”

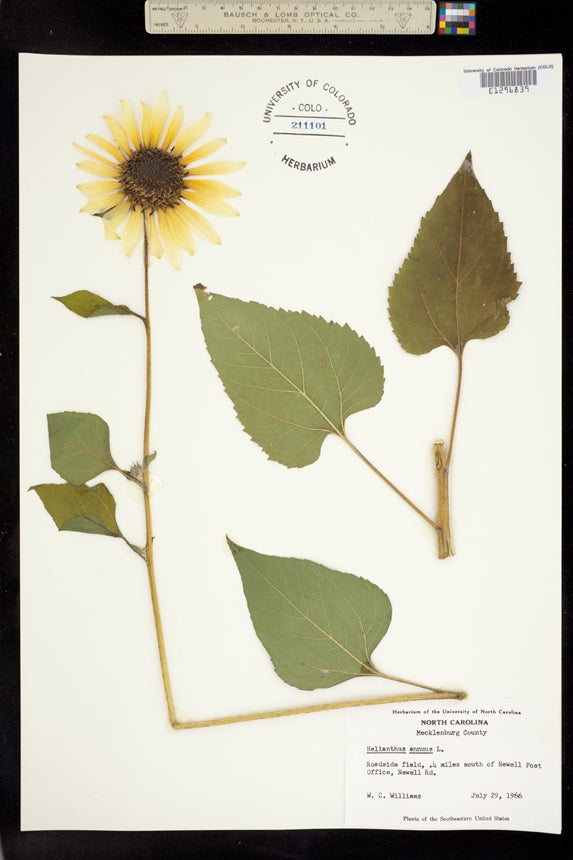

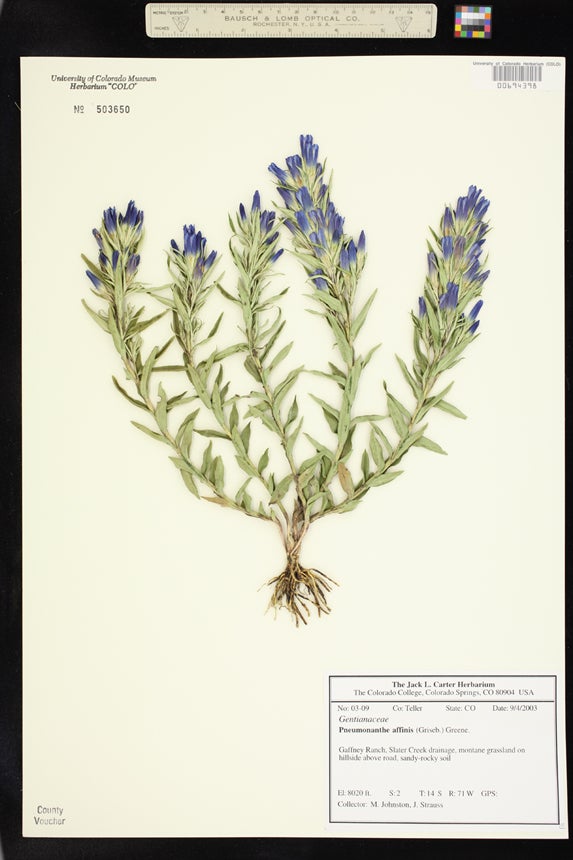

As curator at Herbarium COLO – the botany section of the museum — Tripp is a steward of the collections housed there. “Curation starts with collecting museum vouchers in the field and proceeds through several stages including specimen drying, specimen mounting, identification (usually the longest and most persistent task/challenge), accessioning, filing into cabinetry, then continued curation (repairs, re-identifications, etc.) through time,” she said. Tripp also is a fundraiser, responsible for soliciting major grants.

Although the discovery of new species is exciting, Tripp said her biggest achievements are the scientific papers she has written.

“Science is for naught unless you publish your data and get the word out. The feeling of finally synthesizing results from a project that you have worked on for years is an incredible one and like no other.”

One of her personal and professional goals is to see every species in the genus Ruellia alive, in the field – or “in the cellulose,” as botanists say. “There are probably 350 species of Ruellia on Earth, at least in modern times. Probably only 260 of these are still alive; the others have gone extinct from human activities such as habitat destruction. I have probably searched for something close to 150 of these species in the field and successfully seen 84.”

1. How did you choose biology/botany as a career?

I bought my first backpacking pack in the summer of 1993 (a Lowe Alpine Australis 70, now vintage). I was in middle school and looking for a means to spend as much time outside exploring the natural world as possible. I spent those years of my life in northern Alabama, and remember sitting in the forests in the Sipsey Wilderness, being as still as possible so as to have birds and insects do their thing around me. In college, I immediately declared a major in biology. At the University of North Carolina-Asheville, I took a plethora of amazing classes from amazing professors that sealed the deal: ornithology from Dr. Jim Petranka, entomology from Dr. Tim Forrest, and botany from Dr. David Clarke. David, now a close colleague and friend, was particularly inspiring. He used to tell crazy stories about leading plant-collecting expeditions to some of the most remote areas remaining on Earth — the tepui highlands of Guyana. The stories were about slogging through cloud forests where it never stops raining with 80-pound backpacks, with buckets and fuel and only the gods-know-what-else strapped to the outside. There were stories about running out of ration four weeks into a six-week expedition with no solutions in sight and stories about setting foot and collecting tropical plants in places no human had, nor will ever again, visit.

In my junior year, I asked David if he ever took students along with him. He said “no,” that it was far too dangerous and risky. I told him too bad—that I was coming on his next trip. That was the start of a long journey exploring the highly endemic botany of the tepuis. I have since participated in or led four major expeditions to never-before traversed landscapes — Mt. Ayanganna, Mt. Wokomung, Maringa Tepui, and Kamakusa Tepui — which yielded something close to 5,000 hard-earned museum voucher specimens (collected usually in duplicates of seven for distribution to worldwide museums). It’s been a wild ride. Boulders have come loose from mountainsides and crushed the hips of our expedition members. Others have had to be evacuated because of various medical emergencies. We’ve treated numerous malaria cases in the field. I can’t count how many times we have been woken in the middle of the night by raging floodwaters, having to abandon camp and transport 3,000 pounds of gear to higher ground before it all washed away. We have lost countless numbers of 5-gallon buckets (in which we pack all of our food) in countless different rivers. We have had numerous boat incidents, including a full-on swamping on the Potaro River that cost us a lot of crucial gear (machetes, chainsaws, tree-climbing spikes, short wave radio equipment, ration) and a week of the expedition’s time. But I loved every moment of it. It began my tropical fever. It was also during my first tepui trip during the summer of 2001 that David told me about an internship opportunity that would eventually launch my career in Acanthaceae systematics.

2. Why haven’t lichens been studied more?

Research on these organisms tends to be about 100 years behind the research of most other organisms. We figured out a long time ago precisely how flowering plants reproduce, but we are still puzzling over this very basic element of natural history in lichens. You would be surprised at the level of uncertainty and disagreement among lichen professionals. I suspect this deficiency can be attributed to comparably less attention given to lichens over the years. Lichens belong to an informal group of organisms commonly referred to as “cryptogams” (translation: hidden reproductive parts). Cryptogams include organisms such as mosses, liverworts and hornworts. Lichens are smaller than most plants, but they are just as complex and intriguing biologically as larger, more macroscopic organisms.

Lichens are found in almost every ecosystem on Earth and will grow on almost any object that remains motionless and/or inert for long enough. In fact, many scientists have considered lichens to be “extremeophiles,” or capable of colonizing harsh and inhospitable landscapes that most other organisms cannot cope with physiologically.

3. Is it common to find a new lichen species and how did you find them?

In North American botany, finding new species of plants is very much an exception, to be sure. But in North American (or anywhere) lichenology, finding new species isn’t all that uncommon. The reason is simply because they have been far less studied than plants. Botanists outnumber lichenologists in western North America by at least 1,000 to 5. Part of the reason I study lichens is because there is still so much left to discover, but comparably far fewer warmer bodies to do the work.

I found both new species of lichens under very memorable occasions. I first set foot onto White Rocks Open Space in June of 2013. I was given a small research grant from the city of Boulder’s Open Space and Mountain Parks program to inventory the lichen biota of this 100-acre sandstone outcropping. The first rock I walked toward on my very first day had growing on it a most awkward lichen with a thick, chalky white thallus and fruiting bodies raised up above the surface of the organism. Viewed from the side, it looked like a miniature forest. I had no idea what it was, though suspected it was special and thus chiseled it off the rock and immediately shoved it into a No. 2 brown paper bag. Fast forward five weeks. I was preparing to leave White Rocks for the last time that field season when my graduate student, Vanessa Díaz, and I stopped just short of our car to photograph and collect one last specimen. As Vanessa was hard at work capturing the right aspect and light for her photograph, I glanced down between my feet and saw something of a scintillating, chartreuse-colored species, and said something to the effect of “what the … is that?” It was yet another lichen that I had never laid eyes on, but one so spectacular that I knew right away it was also special.

I thought it would be fitting to honor the lives and careers of two amazing co-workers (and very good friends) with names for these new species. My colleague James Lendemer (New York Botanical Garden) and I thus named them Candelariella clarkiae (in honor of Dina Clark) andLecidea hoganii (in honor of Tim Hogan). Dina and Tim are the two collections managers at the Herbarium (SEE SIDEBAR). They are also widely regarded as two of the most talented botanists in the state of Colorado. Their contributions to the University of Colorado are immense and immeasurable, making them perfect “substrates” for these new species names.

The discovery of Candelariella clarkiae and Lecidea hoganii is noteworthy for at least two reasons. First, these species were found within a densely populated and developed region of the Front Range of the Southern Rocky Mountains: the Boulder-Denver-Longmont urban triangle. Second, these two new species are apparently restricted and endemic to rare outcroppings of Fox Hills sandstone, which derives from the Cretaceous and is exposed to the Earth’s surface at various locations between Arkansas and Canada. In the Front Range, exposed Fox Hills sandstone is quite rare, but obviously very important from a biodiversity standpoint. This lichen research within the city limits of Boulder thus highlights the overall ecological significance of open spaces throughout the United States, particularly in densely populated urban areas. In this case, the discoveries were made within a 10-minute drive of the University of Colorado.

4. You mentioned your interest in Acanthaceae. Why were you drawn to these plants?

I’m professionally trained as a botanist with expertise in the plant family Acanthaceae, and discovered lichens much later in life. Funny enough, my life in Acanthaceae began on the side of a tepui, where no Acanths actually grow. Over our usual expedition lunch of salt biscuits, peanut butter, and guava jam, David told me about a one-year internship opportunity with a woman named Lucinda in Philadelphia. The “Flora of Pennsylvania” internship was a joint position between the Morris Arboretum of the University of Pennsylvania and the Academy of Natural Sciences in downtown Philadelphia, which is the oldest natural history museum in the Western Hemisphere. My job as an intern was to devise an independent research project on some aspect of the state flora. That sounded fine, except for my recent tropical botany disease. Pennsylvania hasn’t been tropical since the Eocene. So there I was, trying to devise a project that investigated some aspect of the plants of Pennsylvania, but seriously afflicted by tropical botany.

I needed a group of plants that was both tropical and temperate (and one that occurred specifically in Pennsylvania). I also quested after a group of plants that was relatively widespread across the planet because, if this whole gig was to work out for the long term, I wanted an excuse to travel to distant locations. At the time, I was also interested in rare species and conservation biology, and hot on big, sexy flowers. Lucinda McDade, curator of the Philadelphia Herbarium at the Academy, happened to work on some plant family named Acanthaceae, so I checked it out in the Academy herbarium. Enter the genus Ruellia: globally distributed and reaching its northern limit of distribution in Pennsylvania where species are rare or endangered. It had gaudy, beautiful flowers. And nobody else was actively working on it. I asked Lucinda if I could work on the genus and she graciously welcomed me to team Acanthaceae.

5. Do you have other interests or hobbies outside of botany?

Sometimes I wish that I had no other interests or hobbies. Life would be much simpler, and I could then focus all of my time on research. But alas, I spend much of my free mental space devising new ways of packing mucho activities into a seven-day week. I love sports: trail running, soccer, rowing and, most recently, I have developed a severe tennis addiction. I ride my bicycle to work to and from Lefthand Canyon as much as possible. Cycling is probably my favorite sport. For me, an active body is an active brain. I also love working with my hands. If I weren’t a professional biologist, I would have been a carpenter, or some sort of engineer. Or maybe a meteorologist. I cook a lot and play my instruments when I can. When the weather holds, I do as much fieldwork and exploring as possible in the southern Rockies, in the southern Appalachians, and across the world. Other than the above, I spend most of my “free” hours hovering over microscopes in my home lab, usually while streaming some football game or tennis match on a laptop.

Top row: Lichens come in all sorts of fascinating shapes and colors, as witnessed by these specimens, including the two new species Tripp recently found, Lecidea hoganii (2nd photo, named for Tim Hogan) and Candelariella clarkiae (4th photo, named for Dina Clark). (Top row of photos courtesy Erin Tripp)

Bottom row from left: Specimens in the Herbarium include Echinocereus triglochidiatus (commonly known as a Hedgehog cactus) found near Penrose, Colorado; Helianthus annuus L. (common sunflower) found in North Carolina; and Pneumonanthe affinis (commonly known as Bottle Gentian) found in Teller County, Colorado. (Bottom row of photos courtesy Dina Clark)