Five questions for Maria Elena Buszek

Stitching and sewing have been part of Maria Elena Buszek’s life for as long as she can remember. Her seamstress mother and aunts grew up sewing, too, in a tiny pueblo of Spain. She learned to crochet from the Polish grandmother on her father’s side. And now she has two daughters to carry on the tradition.

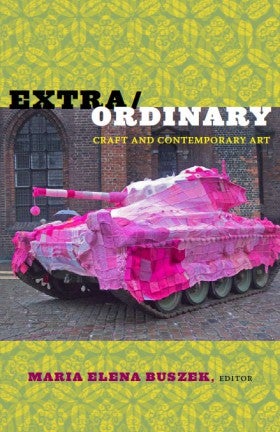

An associate professor of art history in the College of Arts and Media at the University of Colorado Denver, she worked at tying together several threads in an anthology, “Extra/Ordinary: Craft and Contemporary Art” (Duke University Press). As editor of the book, published this spring, she culled the work of several scholars who examine the ways craft is applied in unconventional ways to make big artistic statements. A critic and curator, Buszek also is author of “Pin-Up Grrrls: Feminism, Sexuality, Popular Culture.”

“I teach fairly traditional art history,” she says. “I’m not teaching pin-ups, not teaching craft necessarily. But I do teach how these approaches matter equally – whether we’re looking at Picasso’s paintings, or the advertisings he was clipping into his collages – as statements of artistic culture.”

Buszek earned her master’s degree and doctorate from the University of Kansas; bachelor’s degree from Creighton University. Born and raised in Detroit, she lived in Nebraska, Kansas and Missouri before moving to Colorado last year. Away from her teaching and research, she enjoys spending time with her husband and daughters exploring their new home state, including occasional detours into used record stores.

1. What inspired you to take on the editing of this anthology, “Extra/Ordinary”?

After my first book came out, I was drawn to the emerging generation of artists who were showing in major galleries and museums – but were choosing fiber as their medium. Craft media is something a lot of people associate with the home, but these artists create amazing, thoughtful work. These media are very familiar. Anyone can look around right now and see cloth, ceramic, wood, whether they’ve paid much attention to it or not. Audiences are being asked to look at these tremendously ordinary materials in different ways that are not mundane or ordinary.

2. How do the challenges of writing a book compare with the challenges of editing a book written by others?

People told me that editing an anthology is more work than writing a monograph on your own. That didn’t make sense to me, but I understand why they say that now!

It’s hard enough to manage yourself as a scholar – stay on time, on task, meet deadlines – but when you’re trying to manage 15 other scholars who are also overextending themselves, it’s the experience of herding cats. With art historians, we’re not just managing our own stuff, but also managing the schedules of all the artists, all the galleries, all the museums we need illustrations from. So I’m managing about 15 other people who are each managing about 10 people. It can be a little maddening. The hardest thing to deal with was serving more as an administrator than a scholar.

3. Your book “Pin-Up Grrrls” certainly took on provocative material. What reaction did you receive from colleagues in academia? Was it different from general reaction?

The book is the secret feminist history of the pin-up. It began as my dissertation in a fairly traditional art history program, and there were already raised eyebrows. The fact that I wanted to talk about pop culture as much as the art gallery world made it that much more difficult. They were very suspicious about whether this could be sufficiently scholarly, and they didn’t think it could be feminist – the general consensus was that the idea of a feminist pin-up was an oxymoron.

The biggest surprise for me is that once I shopped the dissertation to publishers, the response was almost the opposite: “Finally, someone is talking about this!” A lot of feminist scholars said they’d felt guilty for being interested in the topic. So I was pleased and shocked to find that the response was positive. The book is in its third printing, which is tremendously gratifying.

4. What does it mean to be a feminist in 2011?

That’s a huge question. I guess the short, stupid answer is that a feminist believes that gender inequality still exists – and is willing to do something to change that fact. We’re living in an era – and it’s not a new concept or unique to our moment – where “feminism” is often considered a bad word. There are caricatures in the media that never really existed, or they’re extreme constructions of what feminism represents. Part of the reason I tend to define and consider it broadly is that there’s always been a million ways to battle for what the activism should look like.

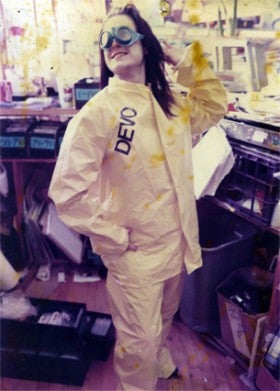

Maria Elena Buszek, circa 1990, modeling a Devo stage costume at the Omaha record shop where she worked as a student. The CU Denver associate professor is at work on a project about contemporary activist art and popular music. (Photo courtesy Maria Elena Buszek)

As someone who’s a pop culture scholar, I’m always having to tell students, “Just because you’re a fan of ‘Sex and the City’ does not make you a feminist.” What are the characters or producers doing that’s trying to change people’s lives? That’s at the root of what feminism always has been and always will be.

5. Do you have another book project in the works?

I’m at work on a third book, which is relating to popular music and contemporary art. I’m going back to my own history on lots of levels: I grew up in a house where we didn’t go to museums or galleries, but my dad’s a musician and an avid reader of the history of music. I grew up collecting music and working in record stores.

It seemed to me that over the last 20 or 30 years, there were artists referencing popular music in ways that art historians don’t understand. There’s this whole body of work by young Latinos that references Morrissey and the Smiths. I’m going to explain that.

I also wrote a book chapter for “Punkademics,” an upcoming anthology about punk rock in academia. Growing up a music fan and someone who was part of punk culture, it made me a feminist and taught me the foundations of art history by accident.