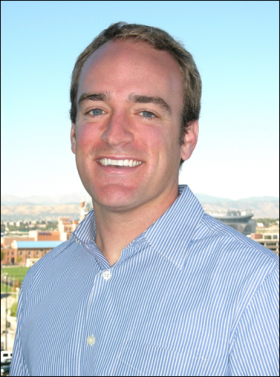

Five questions for Jeremy Németh

Perhaps Jeremy Németh's interest in urban design began in preschool, where he would spend entire days building wooden block towers taller than his classmates. Later he understood he was good at math and science, but also was interested in humans, perceptions and relationships. Architecture seemed like a good fit and he majored in the subject at the University of California, Berkeley. During his junior year, while studying abroad in Italy, he realized he was fascinated by the urban scale and the relationships between people and the spaces between buildings.

"I was less interested in designing interiors and understanding structural loads than I was in understanding how people interact in public parks, sidewalks and social spaces," he says.

At the urging of one of his professors, he received a master's degree in urban design at University College London. He worked for three years as an urban designer in southern California but found that while clients wanted something interesting and different, arcane regulations stifled creativity. Inevitably, he says, the designers re-created "the same lifeless subdivision or the same multi-unit complex, or the same neighborhood layout."

Németh entered the Ph.D. program at Rutgers University, which focused on planning and policy. After graduation, he wanted to teach in a planning program housed in a design college. The University of Colorado Denver – and its College of Architecture and Planning (CAP) – stood out.

"And Denver fascinated me," he says. "There is a real progressive planning and urban politics culture here. While I was out here for my interview in 2007, I remember looking out the window of my hotel and counting five cranes on the horizon. Things are happening here, and I wanted to be a part of it."

Németh is an assistant professor of planning and design and director of the master of urban design program. He teaches core courses in the master of urban and regional planning program and advises about 50 students. His favorite courses include design studios where classes work with community groups to help develop neighborhood plans. A few years ago, he led a team of 14 graduate students in designing plans for the $470 million Denver Union Station redevelopment project, which will be the central hub of the FasTracks system. The students spent 15 weeks gathering data and talking to interested parties. Four plans were devised; many of those components remain in the final design for the project, which is nearing the groundbreaking phase. The project won several awards.

— Cynthia Pasquale

1. Recently you published research on security zones in public areas. What did you find and what are you working on now?

There was another casualty of 9/11, one with perhaps even greater impact for citizens not directly affected by the attacks on New York's World Trade Center – the shutting down and fencing off of some of our most important public spaces and the emergence of an "architecture of fear."

Any visit to Washington, D.C., London or New York City reveals that our most open, diverse and exciting downtowns have become virtual police states. Those who "plan" security zones do so with virtually no public input or consideration of the surrounding architecture and landscape.

While security zones are an easy way for authorities to appear proactive, by limiting access and closing off space, we reduce the potential for more "eyes on the street" to catch possible terror acts in progress. The safest places are often those where residents and visitors have easy access.

I am continuing my work on security in cities, trying to find the most effective ways to balance need for security with the imperative of civil liberties and personal freedoms. Although I've published several pieces in scholarly journals, my focus now is on public scholarship: I've written several op-eds in nationally syndicated newspapers in recent weeks (including The Denver Post).

I am also looking at the impact of the new medical marijuana laws on cities around the United States and Denver in particular. Colorado has legalized medical marijuana, but cities have been left to develop their own zoning and operation ordinances that control where clinics and grow operations can be located. We are helping craft a model ordinance that can balance the concerns of neighborhoods (which feel clinics degrade the areas and reduce property values), patients (who need easy access), dispensary owners (who want to make money) and policy makers (who recognize millions of tax and licensing dollars can be made by regulating medical marijuana).

Second, I am looking at how to plan for "smart decline" instead of "smart growth." Most cities have been concerned for years with growing sustainably, but cities like Detroit, St. Louis and other Rustbelt cities are losing population precipitously. How do we plan for decline when all we know is that "growth is good"?

Third, I am working on a project to understand how to deal with the massive amounts of underutilized spaces in downtown Denver. For example, if we turned half of our surface parking lots into green spaces or community gardens, we would save millions of dollars in storm-water infrastructure and create landscapes that serve as amenities for our public.

Fourth, I am looking at the role of technology on everyday planning processes. How might Facebook, Foursquare, Twitter and mobile technologies such as iPhones change the way people understand and inhabit the city? How might planners harness these technologies and engage a broader citizenry?

2. What would you consider some of the good aspects of urban planning in Denver? What about the not-so-good?

I think what makes Denver so special is its neighborhoods. One can live a mile or two from downtown and not pay too much in rent or mortgage. I love that each neighborhood has embedded retail (along former streetcar lines) like South Pearl Street in West Washington Park, South Gaylord Street in Washington Park, South Broadway in Baker, 32nd, Lowell, Tennyson, in Highland, and the list goes on and on. Denver's Capitol Hill is, in my humble opinion, a world-class neighborhood. You couldn't create that vibrancy if you tried! The diverse mix of students and long-term residents, the combination of chains and local establishments, of large apartment buildings and single family mansions. The residents are so active, so engaged. We rarely go downtown: We feel the neighborhood bars and restaurants have just as much, if not more, life to them. And we own a great 1920s bungalow in Congress Park and we feel like we've got the best of both worlds: urban and suburban living at its best. In terms of new projects, I think the RiNo (River North Art District) and the Riverfront Park/Commons Park areas are great successes. I love the feeling in both of those places.

On the other hand, we have a mismatch between services and residents in downtown – there is not one grocery store downtown or in the Lower Highlands area besides the King Soopers on Speer. And I get so frustrated at the lack of walkability in Denver. Try crossing Speer Boulevard to get from the architecture and planning building to the main Auraria Campus. You better be a world-class sprinter to get across the 10 lanes of traffic. How about a pedestrian bridge for the thousands and thousands of students that cross these streets every day?

3. If you could plan a city from the ground up, what would it look like?

That is a really hard question. We have entire courses devoted to "the good city" and people smarter than I have spent their lives trying to understand the workings of the world's best cities. Instead, I love already existing cities, precisely because they are not perfect. That's why I love Capitol Hill. I am also attracted to the margins, the edges of cities and societies, the less popular but just as valuable spaces that comprise the authentic city. These places are waning and that worries me. Most of my work focuses on how we can limit the powerful effects of privatization that limit real social interaction. Because I believe open, inclusive spaces increase empathy among disparate factions. We might not liketo see homeless people on our way to work, but their presence forces us to acknowledge that they exist and that we live in a society that is OK with allowing people to go without a home. I love the messiness of cities; sanitized, clean spaces scare me.

4. What do you like to do when you're not thinking about urban design?

My favorite thing to do is meet up with friends and watch sports, go to dinner, or just talk. I love Cal (Berkeley) sports and the Pac-10 and I love college sports in general. I played baseball at Berkeley and you can often catch me talking sports with friends or going to a Rockies game. I also read a lot: I love Dave Eggers' books and I am currently fascinated with Roberto Bolano – I'm wading my way through his 800-plus-page book 2666. I love to play golf at Denver's public courses (especially Wellshire), and I am really, really into good food and good beer. I love going for walks with my wife, Leslie, and my daughter, Marin, who is only 3 weeks old. If I miss a day with either of them, I feel like I am going to miss out on something wonderful. We always have such a great time together. They are my buddies.

5. If this were not your job, what would you like to be doing? Why?

I would be a food writer who travels around the world exploring different cuisines, but instead of restaurants I would go to people's houses to get authentic, home-cooked meals. Think Anthony Bourdain but with a heavier focus on the everyday foods cooked by everyday people. I love to travel with my family and we generally spend our entire days wandering around, exploring sites and planning where we'll eat next. We often sit down to lunch and the discussion revolves around where we'll be eating dinner that evening. We've been to many, many countries together, and all our trips have been chosen based on whether we like the cuisine.