Five questions for Phillip Morris

The University of Colorado Colorado Springs, which has been designated as a military-friendly institution for the past five years by GI Jobs Magazine, has 1,335 students enrolled who use education benefits associated with military service. That number is growing, says Phillip Morris, who directs the campus’s Office of Veteran and Military Student Affairs, so it is important to provide a high level of support services for military members and veterans.

His passion for working with veterans stems from his own -- and his family’s -- military service. Morris enlisted in the Army after he graduated from high school to “gain maturity and strength to seek a scholarship to play college basketball.” During the three-year enlistment, he spent a year in Iraq, and after he left the service, he received a full scholarship to play basketball at Concord University.

His grandfather served in the Army in Germany in World War II and his father was a U.S. Marine in Vietnam. “In 2006, my father worked around the clock in the senate campaign of former U.S. Sen. Jim Webb, who he served with in Vietnam,” Morris says. As a senator, Webb authored and introduced the Post 9/11 GI Bill as legislation. “For many reasons I should credit my father for successes in my life, including my current position. The Post 9/11 GI Bill is vastly more complex and comprehensive than the previous iteration, and colleges and universities increased veteran benefits personnel to accommodate the growing numbers of students using the modern GI Bill. Thanks, Dad!”

Before he moved into his current UCCS position more than a year ago, he was the project director of the UCCS SoColo Reach, which encourages area youth to enroll in colleges and universities in the region. He also worked as a veteran and military student orientation coordinator and taught a statistics and research methods course in the College of Education.

Before that, Morris was a graduate student working as a research fellow at the University of Florida. He and his wife, Cerian Gibbes, whom he met during graduate school, were hired by UCCS at the same time.

Although he loves Colorado outdoor activities – particularly mountain biking – a little bit of his heart still resides in Florida. “Between the two of us, my wife and I have five university degrees from the University of Florida Gainesville,” he says. “I will be a lifelong Gator supporter and fan.”

1. You have degrees in political science and geography and a Ph.D. in education administration. Why did you choose a career in higher education?

For my master’s thesis project, I worked with St. Petersburg College on an environmental scan of their student population to determine their market penetration, trade area, and drive-time analysis. The goal was to improve enrollment management from a geographic perspective. During this project, my thesis director, Dr. Grant Thrall, suggested that I get a minor in education and planted the seed for university administration. He once told me that I would be a good administrator because I am affable. It was an odd comment, but I did take his advice and pursued a minor in higher education.

The first class I took was called “Community Colleges of America.” This course was taught by Professor Dale Campbell, who ended up becoming a very influential person in my life and a great friend and mentor. For the community colleges class, I was encouraged to apply for a Ph.D. fellowship and fell in love with studying higher education. During my time with Dr. Campbell at UF, I worked in the Institute of Higher Education and Community College Leadership Program. One of my primary duties was organizing a national best practices awards conference for community colleges, called The Community College Futures Assembly.

2. What are some of the challenges that veterans face in higher ed today, and in what ways has the Office of Veteran and Military Affairs been able to help vets overcome these obstacles?

There are myriad issues that veterans can face as students. I certainly don’t want to paint a broad-brush picture when discussing veterans, because veterans are as diverse as any group of students. I am also careful not to discount service members’ experiences because they did or did not serve in what we traditionally think of as combat positions. So, when we talk about veterans’ experiences, we discuss common struggles and conditions.

Many of our students have served in a combat environment, so they may have lingering effects from the exposure. I have heard this described in terms of mindset: battle mind versus home mind. In a constant-threat environment, survival is contingent upon being constantly alert and aware of surroundings, exerting targeted aggression, trusting your comrades, and responding quickly to perceived threats. Transitioning this survival mindset to the classroom can result in miscommunications, difficulties paying attention, and a general lack of trust in fellow students and instructors.

Other feelings that veterans may be dealing with are remorse over the death and destruction they witnessed. Post-traumatic stress is quite common – although by no means universal. Anyone experiencing PTS may have an exaggerated startle response to loud noises or abruptness, and may be constantly reliving traumatic experiences in their thinking. People not dealing with this type of stress quickly refocus when a door slams or a book drops to the floor, but the process of refocusing may take much longer for someone with PTS. Everyone adjusts differently.

Military deployment - combat or not - can be extremely tough on families. Many times service members have an idealized version of home, and family challenges play a huge role in how veterans adjustment. Many of our service men and women have been on multiple deployments and their families have carried a heavy burden. Other factors that play out in the classroom are issues such as sleep disturbance, substance abuse, or sexual trauma. All of these issues are more common than we would like, and as you can imagine, all take a huge toll on concentration.

I think the most universal issue that veterans deal with is the loss of identity and purpose in transitioning out of the military. This was an issue that I struggled with. When you lose your entire framework of thinking and being, you can easily begin to wonder what your purpose is, or cling to military ways out of habit. Throw on top of this a huge adjustment in expectations and difficulties, sometimes major, with the bureaucracies of the Veterans Administration and the university, and veterans can be very dispirited and have trouble finding reasons to try. It is also important to realize that veterans may not know how, where, or be willing to ask for help. Asking for help or admitting that you are hurting is not the military way.

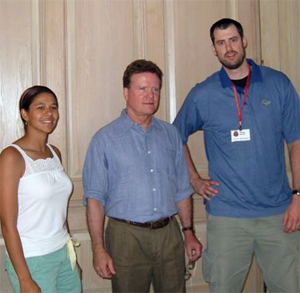

From left, Dr. Cerian Gibbes, assistant professor of Geography at UCCS (Phillip’s wife), former Sen. Jim Webb, and Morris.

My office is doing our best to educate veterans and faculty members about these issues. I always encourage veterans to learn more about themselves in the education process and prepare themselves to be successful by not being too proud to ask for help. I like to tell our vets, “Save your pride for graduation day.” We have implemented an orientation program at UCCS for veterans and military members to help spread this message and make sure everyone has everything in line to receive benefits. We are the first people that these folks interact with as they come to UCCS, and I try to make a point to introduce myself and our office as a welcoming and nurturing place.

Another very significant support structure that we have worked on is promoting and developing the Student Veterans Organization. There are some truly remarkable student leaders working diligently to promote an inclusive, welcoming environment at UCCS. I am very proud of the current and past club leadership team. They all care deeply about fellow veterans, and with a little support from our office, have made leaps and bounds in terms of impact on campus. I am really looking forward to seeing what they accomplish in the future.

3. Doesn’t the structure learned in the military help make veterans better students?

Yes, but this is a case-by-case thing. The rigid structure of the military lifestyle promotes discipline, timeliness, professionalism, and a mission-driven approach. But this approach doesn’t always translate well when the mission is not clearly defined. From studying higher education and student development, I know that ambiguity is part of the cognitive development process for college students, and, generally speaking, the goal of the college experience is taking students from simple to complex ways of thinking. The intensive training that many of our veterans undergo is based on the concept of “stick to your protocol – it can save your life,” so the absence of protocol is difficult for some veterans to understand.

One of the greatest predictors of academic success for veterans is the rank they were when they separated. For the younger veterans, even if they had a high level of responsibility, likely they were always directed and were never asked their opinion and made very few choices for themselves. For these students, the wide-open structure of college is a lot to deal with and may contribute to struggling with ambiguity. My goal is to help all student veterans become better self-advocates, to ask for clarity and help when they need it, and to be open to ambiguity and developing more complex ways of thinking and communicating.

4. One of your goals is to help faculty and staff better understand challenges veterans face. How will you do this?

We are educating faculty and staff through a program we call VETS – Veteran Educators Training and Support program. In the program we discuss the issues veterans are dealing with and try to promote veteran cultural competence. Through this process we are creating a network of supportive staff and faculty on campus.

Another initiative of our office is working to develop an advisory board of faculty and staff members that can help promote veterans’ issues on campus and inform the overall university strategy for maximizing the success of our student veterans. We also encourage all faculty and staff to get involved in activities sponsored by our office and the Student Veteran Organization on campus. We have a full week of events planned for 2013 veteran’s week.

5. Is there a specific time in your own Army experience that has special meaning for you?

Morris helped Fareed Essa and his family come to the United States after Fareed, who was an interpreter for the U.S. military in Iraq, received death threats for working with Americans.

After returning from Iraq in 2004, I learned from a captain that I worked with during my deployment that one of our interpreters, a local Iraqi named Fareed, was in serious danger because of his work with U.S. forces. During my year in Iraq, Fareed distinguished himself as an excellent interpreter with remarkable interpersonal skills. Fareed was the most professional and first-chosen interpreter for combat and civil operations and just a wonderful person. Walt Coleman, the captain who I worked with in the Civil Military Operation Center, found out that Fareed had to move his family from place to place to avoid terror threats and assassination attempts. Walt asked if I would help him develop a residency application for Fareed and his family. After two long years of work, Fareed arrived in Charlotte, N.C., with permanent residency for himself and his family. Walt was determined to get Fareed and his family out of danger and I admire him greatly for his determination and leadership.

Looking back on my OIF experience, helping Fareed and his family is the thing that I am most proud of. Fareed and family are doing well. We speak on the phone often and I make a point to fly through Charlotte when traveling to the East Coast. Fareed will be a lifelong friend. It makes me smile to think about Fareed’s young children doing well in school, playing soccer, and living healthy lives in Charlotte.